Work

Early Life

In the early days Noongar men and women worked in many different kinds of employment. One of the first records of Noongar working was in the Guilford community in 1841. Two Noongar people, Molly Dobbin and Djoogan, became Police Constables.

Noongar men photographed at Guildford in 1901 during a visit to WA by the Duke of York and Duchess of Cornwall. Courtesy of State Library of Western Australia, The Battye Library

Bessy Flower was born in 1851 in King George’s Sound, Albany. Her parents worked for Henry and Ann Camfield, who set-up an Anglican School in 1852, aimed at civilizing and Christianizing Noongar children. The school became known as ‘Annesfield’. Bessy was educated there, along with her siblings, until she was 16.

She spoke French, played the harmonium (similar to a reed organ) and chess. In 1864, she was sent to a Church of England ‘model school’ in Sydney, where she excelled at singing and piano. On returning to Annesfield in 1866, Bessy became a teacher’s assistant and a role-model to younger Noongar children. She also worked as an organist at a local Anglican Church.

Later Life

In later years, Noongar people were mainly employed as labourers and domestic workers undertaking the following work:

- Clearing land

- Domestic service

- Farming

- Guiding European expeditions

- Hunting and selling rabbit, possum and kangaroo skins

- Shearing

- Shepherds

- Tracking

- Whaling (Albany)

“We’d go from farm to farm, farm to farm by horse and cart doing the work … Burning up, stick picking, poison grubbing – all the jobs.”

Elvie Eades Riley, Noongar Elder

‘Uncle Ken Riley used to organise a contract for poison grubbing or stick picking. Then he’d round up the boys, the number required to do the job, and off we’d go – anyone old enough to go … I really miss it because everyone was together. It wasn’t easy, it was hard work, but it was made fun by our Noongar attitude towards things – finding the humorous side to everything.’

Craig McVee, Noongar Elder

Often Noongar people were not paid for their work. Some were offered a slaughtered sheep and a place to camp in return for labour. If there were wages, these were often paid into government-run trust accounts. Noongars (and other Aboriginal people) were subsequently unable to access their own money. These funds are known as ‘Stolen Wages’.

The following is a copy of a letter written by the Chief Protector of Aborigines in 1927. In the letter he refers to Janie Collard (Shaw’s) bank account. This is an example of the Stolen Wages that many Noongar were deprived of.

11 November 1927

The Officer in Charge

Police Station

Beverley

Will you please issue to Mrs M.A. Mott of Brookford, Brookton, a single permit for the employment halfcaste Janie Shaw wages 5/- (shillings) direct to Janie and 5/- to be forwarded to this department. The permit should be issued free and endorsed “Fee Paid at head office”CHIEF PROTECTOR OF ABORIGINES

26 October, 1927

Mrs M A Mott

Brookford

BROOKTON

Dear Madam

Your letter of the 24 inst. Re Janie Shaw just received.

Perhaps I did not explain the matter sufficiently. In addition to the 10/- weekly payable by you, you would be required to provide the girl’s working clothes and boots, bedding and reasonable medical attendance. If Janie required a “best” dress, hat or shoes, etc., such might be purchased by her from your banking account kept at this office. She already has a little in hand.

Yours faithfully

CHIEF PROTECTOR OF ABORIGINES

Noongar people are still fighting to be paid back Stolen Wages. NB. On the 6th March, 2012, the West Australian government announced that it would pay reparations of up to $2,000 to Aboriginal people who had their wages withheld in the years prior to 1972. Those Noongar people born before 1958 are required to provide evidence that their entitlements were withheld from them. The government said that most of the records and documentation about Noongar wages held in trust have been lost.

Australia’s Basic Wage for the Worker

Noongar people contributed greatly to the development of the south-west and to the war effort. During the World Wars, many of our men enlisted as soldiers and fought overseas. As many European workers were abroad during these years, record numbers of Noongar women and men were employed in the south-west.

Noongar people were paid meager sums of money for long days and hard work. To put into perspective the wages paid to many Noongar people working in the South-West. In 1919, Billy Hughes appointed a commission to reconsider the basic wage of the worker – a family with three children needed £5.16s which was 30c more than the current minimum wage. For most of the 1920s, the average wage for an Australian worker was £9.30s.

Although wages were low, prices and taxes were comparatively low. By 1928 Australians had 500,000 cars, about 300,000 radios and telephones. Australia ranked among the top five nations in car ownership. Almost every family had a radio. Many Australians were enjoying a fairly good lifestyle such as going to the cinemas, using a washing machine and an oven to cook in.

Noongar people lived on the outskirts of towns in the bush and made their own camps. There was no running water, showers, washing machines or ovens to cook in. They were barely surviving and able to feed their families.

An excerpt from an interview in ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy’, 2004 from Collard, Harben and van den Berg:

When my mum Jane and dad Fred were living in and around Brookton in the early 1920s both worked very hard, but in return, they were given little monetary reward. They were paid three or four pounds a week and negotiated other necessities like, flour, eggs, a sheep and second-hand clothes for their family.

Throughout WA in the early 1900s most Aboriginal people were rewarded with food, clothing, tobacco in return for their labour in other words “paid in kind”. Most of our lives were spent working on the farms, clearing the land for the Brookton farmers because the government was giving land to the new settlers.

My grandfather, uncles and aunties and my brothers and myself helped to clear all the Brookton farms and dig the blackboys out, chop the trees down and clear the land. That was most of the work we did, we also dug the wells on the farm and fenced the property. Most of that work was ten bob ($1) for one acre to chop it down and one pound ($2) to two pound ($4) an acre to clear the land, which was pretty heavy, maiden timber.

Most of my life we never stayed long in one place. The settlement, when we left there I must have been around … I was about five or six years old and walked to farms around Walebing and Moora. [My family] headed that way out to Moora, shearing or root picking, whatever they could do [for a few years]. This probably was in the early 1940s. I was pretty young, about eight or nine, but we didn’t mind the walking my brother and I. He was about ten or eleven. There were only two of us …

You know, we lived anywhere, we lived any place. Wherever we found a place to live, we stayed. It was all right on the farm because they had little tin humpies or some little place for the families to live in … I didn’t have much schooling then because we were always on the road, all the time, I suppose. I was about eight. It was in the early ’40s. This was after we lived in a little camp and tent out at Walebing. I was still pretty young then, you know.

I remember sitting at the shearing shed door, where my dad was shearing and watching them shearing and throwing the fleece out on the table I liked watching that, you see.

Noongar Elder Margaret Gentle in Collard, Harben and van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy’, 2004

Many of the older Noongar people had worked all their lives on farms but could not get pensions because they were not recognised as citizens. The situation developed that the very people who had ‘built the country,’ who had cleared the land and fenced the farms, sheared the sheep and worked stock, were denied the basic rights that non-Aboriginal people had. Health care was often denied as they had little money to pay for it.

Noongar people were hard workers, they knew the meaning of work and they had the necessary skills to carry out job tasks. They were exploited by being underpaid and overworked. The idea of a “a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work” was not applied to Noongar people even though Australian’s generally knew how work should be organised, and who should work for what rate of pay. However, this all changed after 1967 and the Citizenship Referendum, Noongar people began to receive equal wages. This only came about through advocacy and struggle by Aboriginal people for over a decade.

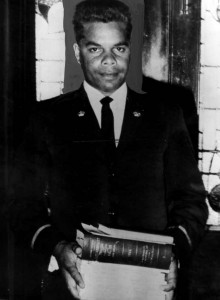

In 1968, Philip Ugle, an ex-farmhand became the first Noongar (and Aboriginal) person to work at Parliament House. The news was reported across Australia. Also that year, Marjory Scott became the first Aboriginal person in Australia to apply for her full pilot license. In 2010, Noongar man Ken Wyatt became the first Aboriginal person elected into the Federal Lower House of Parliament.

Philip Ugle was an ex-farmhand who became the first Noongar (and Aboriginal person) to work at Parliament House. Courtesy of Herald and Weekly Times Ltd.

the World of Work today

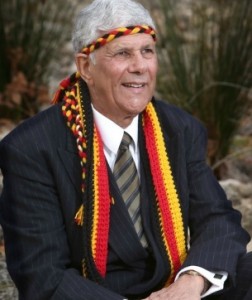

Robert Francis Isaacs PhD OAM JP | Executive Manager Social Lending AHOS, ACCESS, Goodstart and Sole Parent Loans. A leading Noongar Elder with expertise across a wide range of industries including, housing, health, education and politics.

Noongar people are now employed in a range of industries across Australia in the following private and public sectors.

- education

- employment

- mining

- politics

- training

- health

- administration

- finance

- universities

- legal professions

- construction

- business owners

- consultants

- pilots

- Actor

- Film Director’s

- Noongar cultural consultants

- Cultural Entertainers

- housing