Home

For Noongar people the kalil/koolark (home) is where the family heart is. The nature of Noongar homes evolved as the materials available to them changed. In pre-settlement times through to the early 1900s, family groups lived in bough huts –coornts or mia-mia’s– in bush camps. During the 20th century, some Noongars moved to Native Reserves and others camped wherever they could. As well as bough huts, many people lived in tents or in humpies made from iron and hessian bags. Here, we explore the changing nature of Noongar homes.

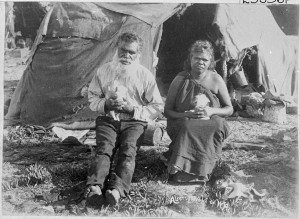

Timbul and Ngilgie at Welshpool Reserve, early 1900s. Courtesy State Library of Western Australia, The Battye Library, 25036P

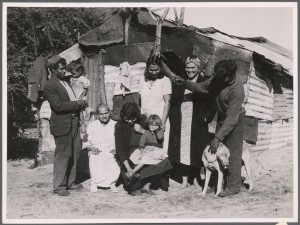

Mrs Worrall and family at Bassendean, 1951. From left: Charlie Nettle (son-in-law) carrying a toddler; Mrs Worrall; Mrs Hedland Jr. (daughter) holding child; Mrs C Nettle (daughter); Doris Mippy (granddaughter); Billy Worrall (son). Courtesy Argus Collection of Photos, State Library of Victoria, H2002.199/87. Photographer Ronald H Armstrong

Karlup & Moort Boodja (Heart – Country)

Kalil/koolark in Noongar mean home or heart-country. Ngany kurt ngany karla – our heart, our home. Joe Northover talks about beautiful Minningup Pool, his ancestral home. He says, ‘This is where all our spirits will end up here. Karla kurliny, we call it, coming home’.

Joe Northover – Minningup pool

Joe Northover talks about Minningup Pool on the Collie River

Audio Transcript

We come here to this place here, Minningup, the Collie River, to share the story of this area or what makes it so special. It is the resting place of the Ngangungudditj walgu, the hairy faced snake. Baalap ngany noyt is our spirit and this is where he rests. You have big bearded full moon at night time you can see him, his spirit there, his beard resting in the water. And we come to this place here today to show respect to him plus also to meet our people because when they pass away this is where we come to talk to them. Not to the cemetery where they are buried but here because their spirits are in this water. This is where all our spirits will end up here. Karla koorliny we call it. Coming home. Ngany kurt, ngany karla – our heart, our home. This, our Beeliargu, is the river people. So that’s why we always come to this Minningup. It’s very important.

This is the important part of the river, of the whole Collie River and the Preston River and the Brunswick River, because he created all them rivers and all the waters but here is the most important because this is where he rest. So whenever we come back now – my cousin died the other day so we come back here, bring his spirit home because this is where he belong here. They will bury him with his mother and you sing out to him. Ngany moort koorliny. Ngany waanginy, dadjinin waanginy kaartdijin djurip. And we come and look there and talk to you old fellow. Your people have come back. Ngany waangkaniny. I talk now. Balap kaartdijin. Listen, listen. Palanni waangkaniny. Ngany moort koorliny noonook. Ngany moort wanjanin. Your people come to rest with you now. Listen old fellow, listen for ’em, bring them home. Karla koorliny. Bring them home and then you sing to them. (Singing in language) And then chuck sand to land in the water so he can smell you. That’s our rules. Beeliargu moort. That’s the river people. That’s why this place important.

Before European contact in 1829, Noongar people lived in our karlup and moved around for hunting and gathering, meetings and ceremonies, in a wider space called a family-run or Noongar moort boodja. We followed familiar paths called moort bidi, a family track. Roaming freely within our country, we lived according to tradition, as we had done for many thousands of years.

Home and European Settlement

With European settlement, Noongar people became prisoners in our own land, forced from our heart-country. Noongars camped where we could in bush or on farm land, but we were often forced off our karlup. After WW1 the government began sub-dividing land for returned servicemen. Yet Noongar returned servicemen were not given the same recognition. This further restricted Noongar people from accessing our karlup. Noongar people were sent to live in town reserves or missions, as more land became fenced off.

Noongar people still continued to follow work where possible and maintain our traditional ways. The seasonal and contract-based nature of farm labour meant most Noongar people had to move constantly to find employment. Despite this situation, the majority of Noongar people continued to follow work within the area of our family-run, maintaining a connection to our home country.

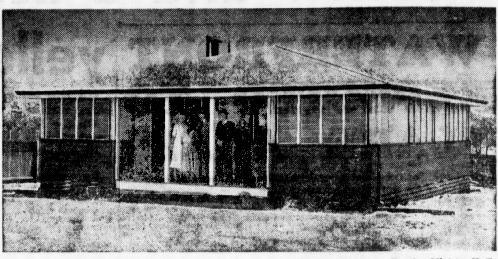

The Department of Housing provided a brief history of housing in the southwest of Western Australia. This included the first metropolitan house for an Aboriginal family in Eden Hill, wash room facilities at the Merredin Reserve in the 1960s and housing in East Perth in the 1960s.

The first metropolitan house for an Aboriginal family in Eden Hill, 1954. Courtesy of the West Australian

East Perth in the 1960s – known then as ‘the slums’ was mostly populated by Aboriginal families.

Photo courtesy of The West Australian

Types of Homes

We did our best to make our houses as homely as possible. Materials were recycled in creative ways; hessian bags were sewn together to form blankets, or the lining of a tent. Kerosene tins were used to collect and store water. Sunshine milk tins made good lanterns. Brooms were made from bush-materials, to keep mia-mias, humpies and coornts neat and clean. Mia mias and coornts are more traditional Noongar homes. A mia- mia is made of natural bush materials such as sticks and branches, whilst a coornt is built from balga or grass tree rushes. A humpy uses the combined materials of wood, tin and hessian bags.

Camp at Herdsman’s Lake, early 1900s. Courtesy Barr Smith Library, University of Adelaide, MSS 572.994 B32t

I remember a lot of my family lived in their camps in and around Brookton. My Nan used to tell us kids to go and get a nice big bramble each which we used to sweep around the camp. These were our brooms. The camps were always kept clean and tidy. After we would sweep up, Nan would throw water about to wet down the ground. A lot of Noongar families looked after their camps this way.

Sandra Harben, SWALSC, 2013

Family Together

No matter where Noongar people lived, there was a sense of family and togetherness in the camps. This is particularly true when families were faced with the threat of children being taken away to missions and homes. (see Stolen Generations) There was a sense of family in the camps that was wider than the nuclear family.

Joe Northover tells of living ‘in the old railway houses with their big verandahs and family always next to you’. For Gus Ryder it was ‘a humpy alongside the river, with plenty of rabbits and sometimes, duck eggs’.

Although increasing numbers of Noongar families were forcibly removed from their karlup, many Noongar people post-European contact remained living on the traditional moort boodja -family-run. Today, many Noongars choose to live and practice traditional customs, such as hunting and ceremonies, on the land where our ancestors have lived since the beginning of time.

Today, many Noongar people are buying their own homes or renting from various housing providers whilst still maintaining their cultural connections to family, language, hunting and other cultural events.