Noongar Lore

Noongar Words

kaartdijin – knowledge

noonookurt koorliny – you go along

ngulluk koorl koorliny – they can go back

warra wirrin – bad spirit

boolywar – power/powers

quop wirrin – good spirit

manitjimat – white cockatoo

wardang – crow

mat – stock, family, leg

bulyit – little hairy man (spirit)

Wadjemup – Rottnest Island

Noongar men photographed at Guildford in 1901 during a visit to WA by the Duke of York and Duchess of Cornwall.

Courtesy State Library of Western Australia, The Battye Library 471B/3

Noongar people have complex lore and customs pre-dating European contact. Our lore has existed alongside European laws and still does today. The terms ‘lore’ and ‘law’ are sometimes used interchangeably, but ‘law’ refers to written European law. Lore for Noongar people is unwritten and refers to kaartdijin (knowledge), beliefs, rules or customs. Noongar lore is linked to kinship and mutual obligation, sharing and reciprocity. Our lore and customs relate to marriage and trade, access, usage and custodianship of land. Traditionally, it has governed our use of fire, hunting and gathering, and our behaviour regarding family and community. Noongar lore works with nature to protect animals and our environment. Noongar people do not eat animals that have totemic significance with our names. This contributes to assuring biodiversity is maintained and food supplies are always in abundance.

Kaartdijin and lore belongs to Noongar people only and is different from other Aboriginal groups. All of these lores have been transmitted from the Elders, fathers and mothers to their sons and daughters through unknown generations, and are fixed in the minds of Noongar people as sacred and unalterable. Because many parts of Noongar lore are complex it is often misunderstood. Noongar lore is not transcribed from thousands of years of oral history into writing.

Our explanation of Noongar lore is an introduction to some of the main types of acknowledged lore and customs observed by Noongar.

If they go one way, and you go this way, you’re not allowed to meet up otherwise you get into big trouble, you know. And that’s always we kept those lores. Always you kept those lores.

Kayang (Hazel) Brown, oral history, SWALSC, 2008

Lore and Adulthood

Certain Noongar lore belongs solely to either men or women. There are many special places around Noongar boodja (country) that are important to Noongar men and women for ceremonial purposes. We still have cultural recognition for the coming of age from youth into adulthood. Traditionally, secret customs and rituals existed for the passage into manhood and womanhood.

One of the things that Uncle Cliff Humphries talked about was that, that place [Kings Park] was a ceremonial place and more so for the fact that it had a lot of areas where women had special places. It wasn’t his right or my right to know what had taken place there. But he said they often talked about the significance of that place to the women. In Aboriginal way, when women got a special place, that’s a place that’s not necessary to pay attention to [by men], but you have to respect it.

Noongar Elder Sealin Garlett in Collard, Harben and van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy’, 2004

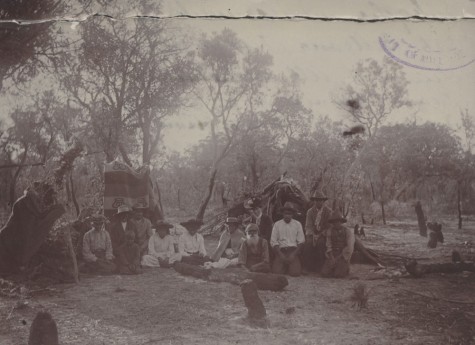

Noongar group, early 1900s. Courtesy State Library of Western Australia, The Battye Library 012523PD

Margaret Drayton talks about growing up as part of the closely knit group of Yued women. Her mother remembered when she was a girl her Granny Sarah Cuimara was a real traditional woman and she used to take the women’s group out for Women’s Lore business.

My mum recalls knowing the traditional roles of food gatherer and regularly going out with her grandmother and with other older women in the family to collect bush foods. … She was taught when it was appropriate to speak and when not to – the main word Granny used to get the attention of the children was nie, which means “listen, stop talking”. Mum used to do the same with her children, and I do it with mine.

Margaret Drayton, oral history, SWALSC, 2011

Noongar Lore and Marriage

Like Aboriginal groups all over Australia, Noongar people have a system of marriage or union that ensured our survival over thousands of years. Traditionally, we developed a rule-based system to avoid intermarriage between close relatives. Groups of families were categorised into separate moieties or kinship groups. Classification into these moieties is determined by descent from our mother (matrilineal) or from our father (patrilineal), depending on the country we came from.[i] Noongar men would travel a long distance to find a wife from another group.

Amateur ethnographer, Daisy Bates describes matrilineal moieties she learned from Jubaitch, a Balluruk Noongar man who had great knowledge of Noongar lore and tradition. The matrilineal kin groups are Manitjimat (white cockatoo) and Wardongmat (crow). ‘Mat‘ means ‘stock, family, leg’. Children inherit the moiety from their mother and must not marry a member of the same skin group. For instance, ‘a Crow man could only marry a Cockatoo woman and vice versa’.[ii] See table below.[iii]

| Male | Female | Offspring |

| Wardungmat | ||

| Ballarruk | Tondarup or Didarruk | Tondarup or Didarruk |

| Nagarnook | Tondarup or Didarruk | Tondarup or Didarruk |

| Manitchmat | ||

| Tondarup | Ballaruk or Nargarnook | Ballaruk or Nagarnook |

| Didarruk | Ballaruk or Nagarnook | Ballaruk or Nagarnook |

| Male | Female | Offspring |

Kayang (Hazel) Brown tells how her uncle married her mother following the death of her father, how it was part of Noongar custom.

We moved around the Borden, Ongerup, Gnowangerup and Needilup area until I was about four years of age. Then we came back to Gnowangerup to live, about 1930. That’s when Freddy Yiller died. My mother then had two children, so Fred Tjinjel Roberts – really the only father I’ve known – he married my mother.

They got legally married about two weeks after Fred Yiller died because that was Noongar way, you know. She was accepted Noongar way, and his brother died, and so he had to look after her. He had to care for her, and for us.

Kim Scott and Hazel Brown, Kayang and Me, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 2005

Jubaitch with his three wives and children at their Bellevue camp, 1904. Jubaitch inherited his third wife, Yoolyeenan (Fanny Shaw), from his elder brother. Daisy Bates is sitting behind Jubaitch. Courtesy Barr Smith Library, University of Adelaide, MSS 572.994 B32t

It was not uncommon for a man to have several wives, either by contracts arranged years before, or by assuming under tribal lore the responsibility for his brother’s widows. Noongar maaman (men) might have had several yok or wives and inherited many kurrlonggur (children), and therefore became the maam or maaman (father). But children always know their bloodline and heritage through their mother.

I had lots of big sisters and brothers. We weren’t all just having the same mother and father. You know a lot of blackfella ways; that was going on for years with Aboriginal people.

Margaret Gentle in Collard, Harben and van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodja Noonookurt Nyininy’, 2004

Elders

In the South-West, yeye or today, as in kura or the past, Noongar boordier or elders play a role as custodians of all knowledges, and in particular “special” knowledges which are to be passed on. Today this continues through intergenerational Noongar interaction using oral and written discourses. As each generation passes on, it is then our and their duty, as the current and future generation of Noongar people, to take on these custodial responsibilities, passing them on to our future generations. These include keeping harmony with social protocols in our past, current and future worlds by ensuring that each successive generation of regional Noongar descendants, be they Whadjuck, Balardong or Minang, are brought up to understand and take their responsibilities and place as active participants and custodians of such ancient katitjin or knowledges.

In contemporary Noongar societies of south Western Australia, these concepts are still evidenced. Noongar Elders are still acknowledged as the custodians of knowledge and wisdom of their boodjar, moort and katitjin, and are responsible for the perpetuation through ongoing communications of Noongar knowledge’s and its application. Elders are recognised by their community, they are not self appointed. Both men and women are acknowledged as Elders. They have as much respect today as they have for many centuries.

Kevin Fitzgerald snr. talks about the role of elders and the adaptation of Noongar lore:

Traditionally, the circle of elders was mostly men. They were given this position in relation to their age and stamp in society. It was a position that was earned, through initiations in lore, like a set of qualifications.

In contemporary society, men and women acknowledge one another and responsibilities are shared. Some of these include teaching, welcome to country and storytelling. This has come about over the past 20 or 30 years, as women have taken on more responsibilities.

Noongar lore has adapted to contemporary society where men and women are equal. We still go out to hunt and we acknowledge Noongar lore but we’ve adapted it to today’s laws and views. We still respect our elders and they still have a lot of decisions to make. They still have a major role to play.

Kevin Fitzgerald snr., oral history, SWALSC, 2011

Lore and Land

Noongar people have always followed lore and customs with respect to the land. We have collective rights through succession or inheritance to particular tracts of land, and Noongar cultural protocol establishes who can and cannot ‘speak for country’ or who can perform ‘welcome to country’. These rights are incapable of being transferred or surrendered. When a Noongar man marries, he has rights to his wife’s country and may visit and hunt on that land. Rights are inherited through family lineage to an area of land, and under Noongar lore and custom, they are respected as sacred. Any digression from this is forbidden and considered a breach in our lore. This lore is a central belief of Noongar culture and formed an integral part of the successful Noongar Native Title claim.

Each Noongar moort (family) had their own land for hunting and gathering purposes and regarded the incursion of others onto it as trespass, although resources were shared freely with neighbours.[iv]

The old Nyungar, the tribal Nyungar, they used to speak with their mob, and travelled with their mob. They would go across one way, then the other mob might want to go across the other way. Well, they pass through and let them go on. Noonookurt koorliny, means they can go through.

If they [stranger]make any bad trouble, they might have a big fight halfway there and the strongest team, well, they say. Ngulluk koorl koorliny – means they can go back.

Elder Tom Bennell RIP, 1978

Len Collard collection

There are circumstances when travel across land boundaries is permitted. This can be an abundance or under-supply of food due to particular environmental conditions, or due to wildfire or for the trade in goods and other cultural purposes. Permission to travel through country was always granted by the local Noongar group; it was custom however, that Noongar people must ask permission from the appropriate bridyer (boss). The travel route through designated areas was also agreed, and it would avoid sacred sites.

Noongar land, often referred to as moort boodja (family run), and the area in which we work, hunt and visit, was protected and managed. This was done with kala (fire). Noongar people periodically burnt off the grass to provide a new crop of sweeter grasses in the season to come. In addition to fire management, we have also used conservation principles in a system of lore related to food.

Lore and Food

Traditionally, Noongar men and women have collaborated with a division of labour, whereby men hunt using kali (boomerang) and gidjee (spear), and women gather food using dowack and wanna or digging sticks. These weapons and tools can only be used by the men and women carrying out the activity. Gathering of kona (native potato), kwordiny (wild carrot), mee-nar (wild onion) and woorine (native yam) is considered the province of women because of the association of some of these foods with fertility. Women have traditionally practised conservation to ensure the production of woorine (yam) by leaving a portion of the plant in the ground. Woorine grounds were extensive and Noongar people returned to them regularly.[v]

….And they [the children] accept, don’t break that, don’t tread on that ant, you know, or don’t kill that bee there or that little djiliyaro, one of our little bees, because you won’t have any quondongs next year or you won’t have any of those little berries and everything like that next year. So you got to look after them.

Bill Webb, oral history, SWALSC, 2008

Underlying all Noongar lore regarding food are principles of conservation and preservation of biodiversity. By practicing this lore the sustainability of plants and animals and the harvesting of them are maintained. Traditionally, no production of vegetables could occur when that plant was bearing seed, and rare foods could not be eaten. Taboos also existed for certain foods. For example, it was considered bad luck for Noongar people to kill particular species that weren’t in abundance.

Lore around the way food is caught and prepared was also observed, and still continues today. If we didn’t abide by the lore, there were consequences. There is also the tradition of elders receiving food first, which is still widely observed and accepted as lore today.

Mrs Averil Dean tells her story about Noongar lore which was passed on to her by her brother Jack. The story she tells is a tribute to him and she called him “our historian“. His story is about the traditional people and how they used to go and catch salmon to feed the whole tribe.

… they had a special man and only one man was allowed to do this. This was tribal lore. They used to have this special man that had … he had to have a beard and the wind had to be blowing in a certain direction. And he’d have to light a fire on the beach. And he’d have to have a fire and make it a smoky fire so that the smoke could blow out. And he used to sit on the beach with his legs crossed and he used to tap his sticks together. And he’d sing, djock, djock, djock.

And then all of a sudden he would see the dolphins start to work. And they’d go around a big school of salmon and they’d go round and round and round and work ’em around like, like a sheep dog does, I suppose, if you say that. And then they used to bring them right in to the beach and they’d go into a real frenzy ’cause they’d be bringing them right in, bring them right down to the beach and then the whole tribe, even children could come in and catch them.

Averil Dean, oral history, SWALSC, 2012

Values

Underpinning Noongar lore is a set of values and a sense of what is kwoba (good) and warra winarch (bad spirit). Linked to this in the spirit world are a corresponding good ancestor, Motogon and an evil ancestor, Djinga. These spirit ancestors are not given any kind of divine worship but they help provide answers to what is right and wrong. To keep social order and codes of morality, Noongar people maintain a set of values conveyed through stories handed down generation after generation with messages of right and wrong.

Dr Richard Walley relates the story about Bullung (pelican) and Bulland (crane):

Bullung and Bulland, which is the Pelican and the Crane; that’s a short little one. They were two brothers and they were both skinny at the time. The Pelican was never, ever big and they were both same shape as the Crane. They went fishing and during this particular fishing expedition, the old Crane stood at one end of the stream and he was looking for the fish and the Pelican stood at the other end.

What happened, the fish would swarm around and the Pelican would grab one. He thought it was only one and he didn’t want to share it. So when old Bulland walked up to him, said, “How are you going”? Bullung said, “Grmmrrmm . . .” and shook his head. He kept the fish in his beak and when another fish came along, he grabbed that one, too. And he’d grab four or five fish in his mouth and the other fella up there, he’s skinny, he’s starving and he’s looking.

How ya going? Any fish down there”? “Grmmrrmm . . .” he kept swallowing these fish. This happened four or five days in a row and then, after a while, old Pelican started looking fat and his beak started to get big. And the other fella, old Bulland, he’s still skinny, up the other end. The other one is still getting little fish here and little fish there and then next thing you know, there was this wild dog came barking and chasing something. As the dog came closer, well the Pelican, he couldn’t fly off as fast as the Crane. The old Crane, he took off flat out ’cause he was pretty fit, but the Pelican, he realised that he was getting fat.

The dog was getting closer and closer to him, and as he tried to fly off, this dog jumped towards him and landed on his back. Then the Crane came back and pecked at the dog, so now, when you look at the Pelican when he takes off, you can see where the claw marks are and the feathers are jagged.

That’s how the Pelican got fat and realised that you have to be very careful in the future. But the Crane still stays very quick and the Pelican is very slow to take off. They were simple little stories like that where you look after yourself, health wise…

Dr Richard Walley in Collard, Harben and van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy’, 2004

Customary Lore or Payback

For many thousands of years we have had our own system of retributive justice or payback. If a lore or custom was broken or violated, appropriate retribution would be carried out. The severity of payback depended on the significance of the lore broken. Payback could occur for offenses such as ‘firing’ the territory of another group, for stealing resources or for taking another man’s wife. In the case of a killing, ‘a man’s death had to be avenged before his spirit could rest. The graveside ceremony was the best place to begin the inquiry, and the direction taken by a beetle disturbed in the digging was closely observed, as was the direction suggested by a wisp of smoke rising from leaves burnt near the grave.’[vi] Payback for lesser offenses usually involved a spearing through the thigh or the offender would be ostracised from the community.

Boylyada Maaman – Medicine man, Healer, Witchdoctor

Powerful men known as Boylyada maaman can be likened to a medicine man, healer or witchdoctor. These men were very influential in Noongar society. Boylyada maaman had powers to heal sickness, cure diseases and foresee events. They could even understand phenomena which may be beyond the understanding of ordinary people. “Issac Scott Nind in Albany noted their skill in treating spear wounds; after carefully removing the barbs, they would sprinkle the wound with medicinal powder and cover it with a soft bark.’[vii]

‘Nowadays not too many people believe in this Boylyada business, but years ago, the old Witchdoctor was very, very clever. This was before the doctors [white] came out. Before, they can do their own healing. Now they [Nyungars] even don’t believe in that. They have their white rules and they forgot about the Noongar (witchdoctor) rules now.’ Elder Tom Bennell RIP

There was always an old Witchdoctor in those days. What they call them they Dembart – Grandfather. Dembart noonook kaataminy koorl djeenaniny nguny djenark minditch – means he (grandfather) must come and have a look at him, he is sick with the debil debil [sic] (devil). This old Witchdoctor, he come and he said djeenaniny, barlung kaya noonook djenark minditch – look, yes he is sick with the bad spirit.

So, I directly got to noonook warbaliny – that means he got to doctor him up, but they only do it when the sun goes down… They could doctor him and all his chest and one another all around with their fingers, they clap their hands together and they draw that spirit that djenark spirit out of him. The Witchdoctor says, Nguny djenark Noonung barmaniny yeye – his bad spirit hit into his body yesterday, then he said, Noonook quop benang. Noonook quop – Well, … he would be up walking around tomorrow morning, good as a gold.

Elder Tom Bennell RIP, 1978, Len Collard collection

To survive European colonisation, Noongar lore has had to change and adapt but it still remains identifiably Noongar. As recently as 2006, the Federal Court of Australia found the acknowledgement of Noongar lore and observance of Noongar custom by Noongar has continued despite the colonisation of Western Australia in 1829.

Rules

Noongar have many rules that govern our behaviour and the safety of self, family and community:

- Noongar people (especially children) are not allowed to see, play amongst or torment the Noongar Spirit Snake, Waugal, as they might get sick or even die. The Waugal is sacred and we don’t desecrate something that is sacred

- Noongar people have protocols to follow when they are around the Waakal’s sacred waterholes. Noongar tell is that when the water is clear “it is all right to take the water, but when it is ‘dark or murky’ the Waakal is swimming around and you must not take any water while he is there

- Noongar people should not draw in the sand after dark because the warra wirrin (bad spirits) will come to you during the night and give you a very restless sleep

- Noongar people don’t whistle at night because we don’t want to alert the warra wirrin (bad spirits) and invite trouble into our lives

- Noongar kids always go in pairs or more when they are travelling around because it is safer, and and if any harm comes to one of them the other can provide assistance. Also, two heads are better than one when it comes to reminding each other of Noongar rules if needed

- Noongar children are to go home before the sun sets; it is not safe for children to be out after dark for the bulyits – little hairy men – will catch them and take them away

- Noongar children should not play with fire because the warra wirrin (bad spirits) will come to you during the night.

Bulyit – [he’s a] little hairy man about two foot high, that means devil, [he will] take the children, must not go out after dark, after 4 p.m. [must] gather them all up and bring them home. Bardee borl bardee koorl barmaniny – that ís before our time, children going out and breaking up all those black boys to get the bardee.

They would then gather them all up and take them home. Koorlongka dookaniny – children cook the bardees when they get home. After 4 o’clock they must not go chasing bardees, they wouldn’t be allowed. They reckon these debil debil [devil devil] will take them away. That is a little bulyit man. As soon as the sun goes down, he starts edging them off and taking them away.

Noongar Elder Tom Bennell RIP, 1978, Len Collard collection

… Noongar people are very spiritual people and you know if you do something, if you kill something for the fun of it then you know something will happen to you so you know you were taught that and you were taught about rules. You know when we sit around a campfire you’re not allowed to whiz the sticks around because you’ll bring the mummaries and woordatjis up. That’s the spirits. So you know growing up in the bush … where the rules were pretty well known.

Trevor Walley, oral history, SWALSC, 2008

Nyungar have protocols to follow when they are around the Waakal’s sacred waterholes. The stories that many Nyungar tell is that when the water is clear “it is all right to take the water, but when it is ‘dark or murky’ the Waakal is swimming around and you must not take any water while he is there”

Bennell 1978a; Winmar 2002; Hayden 2002 in Collard, Harben and van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy’, 2004

References

[i] Bates, D. Aboriginal Perth, Bibulman Biographies and Legends. P.J. Bridge (ed.) Hesperian Press, Carlisle, 1992, p.57

[ii] Bates, D. The Native Tribes of Western Australia. Ed. Isobel White. Canberra NLA, 1985, p.76

[iii] Bates, D. The Native Tribes of Western Australia. Ed. Isobel White. Canberra NLA, 1985, p.76

[iv] Tilbrook, L. (1983). The First South Westerners: Aborigines of South Western Australia, Western Australian College of Advanced Eduction, pp.105, 556

[v] Hallam, S. Fire and Hearth: A Study of Aboriginal Usage and European Usurpation in South-Western Australia. Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, Australia, 1979, p.12

[vi] Green, N. Broken Spears, Aboriginals and Europeans in the southwest of Australia, Focus Education Services, Cottesloe WA, 1984, p.18

[vii] Green, N. Broken Spears, Aboriginals and Europeans in the southwest of Australia, Focus Education Services, Cottesloe WA, 1984, p.18