Spirituality

Noongar Words

maam and yok – men and women

kura – long ago, the past

yey – present

koroboree/kobori – dance

boodja – country

kaartdijin – knowledge

Noongar spirituality lies in the belief of a cultural landscape and the connection between the human and spiritual realms. Everything in our vast landscape has meaning and purpose. Life is a web of inter-relationships where maam and yok (men and women) and nature are partners, and where kura(long ago, the past) is always connected to yey (present). Through our paintings, music and koroboree/kobori (dance) we are paying respect to our ancestral creators, and at the same time, strengthening our belief systems. Noongar connection with nature and boodja (country) signifies a close relationship with spiritual beings associated with the land. We express this through our caring for boodja and observing Noongar lore through an oral tradition of story-telling.

Noongar spirituality is one of many kaartdijin systems within Aboriginal Australia, and like other knowledge systems, there is diversity in our Noongar interpretations.

Dr Noel Nannup on Nyungar Spirituality http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2-k3WGOar_4

The Noongar Creation Period

Noongar Words

babanginy– lightning

bilya/beeliar – river

boya – rock

boroong – rain

koondarnangor – thunder

ngamma – waterhole

pinjar – swamp/lake

Waugyl – Noongar Rainbow serpent

walken – rainbow

Nyitting – Dreaming

The Nyitting or Dreaming means ‘cold,’ ‘cold time’ or ‘ancestral times.’ Noongar people know it as the Creation time. It is the time before time when spirits rose from the earth and descended from the sky to create the land forms and all living things. Nyitting stories laid down the lore for social and moral order and established cultural patterns and customs. Our Noongar Elders have the ability to comprehend the knowledge and to maintain it in an unchanging way. Noongar creation stories can vary from region to region but they are part of the connection between all living things.

At York you can see where the Warkarl (water snake) left a track when he came over the hill. The Warkarl made the rivers, swamps, lakes and waterholes. He came over the hills at York, and his tracks can still be seen. He came down the Avon river to the nanuk (neck) of the river at Guildford, where there is a bend.

When he finished he went to a great underground cave in the river. He did not go on because the water further on was salty. The Warkarl is very important to us Noongar because we believe in the Dreaming.

Noongar Elder, Ralph Winmar, RIP [i]

Author and poet the late Dr Jack Davis, an Aboriginal man who spent most of his life in Noongar booja, wrote the play Kullark (1982). The audience could hear Dr Davis’s version of the local Whadjuck boordier Yagan‘s ceremonial chant which could be heard loud and strong as he pays tribute to the Warrgul [sic] for creating the Noongar universe:

Woolah!

You came, Warrgul,

With a flash of fire and a thunder roar, and

As you came, you flung the earth up to the sky,

You formed the mountain ranges and the undulating plains.

You made a home for me

On Kargattup and Karta Koomba,

You made the beeyol beeyol, the wide clear river,

As you travelled onward to the sea.

And as you went into the sunset,

Two rocks you left to mark your passing,

To tell of your returning

And our affinity

The Waugal or Great Serpent-like Dreamtime Spirit

Noongar Words

waugal – serpent

bilya/beeliar – river

pinjar – swamp/lake

ngamma – waterhole

babanginy – lightning

Waugal or waug means soul, spirit or breath.

The Waugal is the major spirit for Noongar people and central to our beliefs and customs. Waugal has many different spellings, including Waakal, Wagyl, Wawgal, Waugal, Woggal and Waagal. The Waugal is a snake or rainbow serpent recognised by Noongar as the giver of life, maintaining all fresh water sources. It was the Waugal that made Noongar people custodians of the land.

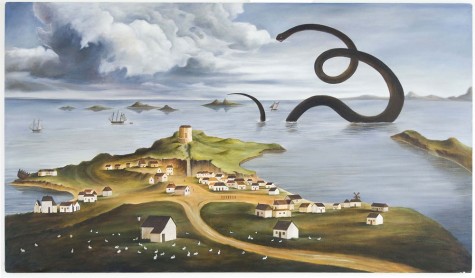

Information from Christopher Pease about this painting.

Noongar people believe that the Waugal dominates the earth and the sky and makes the koondarnangor (thunder), babanginy (lightning) and boroong (rain). During the Nyitting, it created the fresh waterways such as the bilya/beelier (river), pinjar (swamps, lakes) and ngamma (waterhole). The Darling Scarp represents the body of the Waugal, which created the curves and contours of the hills and gullies. As the Waugal slithered over the land, its track shaped the sand dunes, its body scoured out the course of the rivers, where it occasionally stopped for a rest, and created bays and lakes.

The Waugal rose up from Ga-ra-katta (Mt. Eliza at the foot of Kings Park), and formed the Derbarl Yerrigan and the Djarlgarro Beelier (the Swan and Canning rivers). It also created other waterways and landforms around Perth and the south-west of Western Australia. The Waugal also joins up with wetlands such as Herdsman Lake and Lake Monger, and resides deep beneath underground springs.

When the great Waugal created the boodja,he ensured that there was wirrin or spirits to look after the land and all that it encompassed. Some places such as the karda (hills) and ngamar (waterholes), boya (rocks), bilya/beelier (rivers) and boorn (trees) were created as sacred sites and hold wirn (spirits), both wara/mambaritj (bad) and kwop (good).

Hi there I am teaching class two this year and would dearly love to take them on Noongar dreaming journey. I was wondering if you know of where I could source some stories that I could share. Thanks so much Anne-Marie McShannon

The late Noongar Elder, Tom Bennell tells us ‘that Waugal, tha’s a Noongar story many years ago.’ Here he tells us that the Waugal is a water snake:

The Waakal – that’s a carpet snake and there is a dry carpet and a wet carpet snake. The old Waakal that lives in the water, they never let them touch them. Never let the children play with those. They reckon that ís Noongar koorlongka warra wirrinitj warbaniny, the Waakal, you’re not to play with that carpet snake, that ís bad. …

Nitcha barlup Waakal marbukal nyininy – that means he is a harmless carpet snake. He lives in the bush throughout Noongar budjar. But the old water snakes; they never let them touch ’em. … the real water snake oh, he is pretty, that carpet snake. … the Noongar call him Waakal kierp wirrinitj. That means that carpet snake, he belongs to the water.

You mustn’t touch that snake; that’s no good. If you kill that carpet snake noonook barminyiny that Waakal ngulla kierp uart, that means our water dries up – none. That is their history stories and very true too.

Noongar Elder, Tom Bennell, RIP [ii]

Noongar people believe that if you harm resting place of the rainbow serpent or his earthly beings at the place of water then the country would dry up and die.

Noongar Elder, Jack Williams, RIP [iv]

The late Noongar Elder, Ralph Winmar, reinforces the Waugal story in his book Walwalinj – The Hill That Cries:

At York, you can see where the Warkal (water snake) left a track when he came over the hill. The Warkal is the giver of life, he made the rivers, swamps, lakes and waterholes, he maintains the fresh water sources.

Noongar Elder, Ralph Winmar, RIP [iii]

Daisy Bates (amateur anthropologist), who spent many years learning from Noongar people wrote about the Waugal:

‘Waugal was invariably described as feathered, finned, maned and or horny. Residing in certain springs, pools, hills, caves, gorges and trees the Woggal could also be an unfriendly and fearsome guardian spirit. The Woggal’s stations were ‘winnaitch‘ – taboo. The “Waugal” is an aquatic monster … (which) inhabits most deep waters, salt or fresh, and almost every lake or pool is haunted by one or more such monsters … that if an ordinary person was to ask … about the ‘woggal‘ (mythical snake) who lived in a particular tree or cave in his or her Noongar budjar, the Noongar people would more than likely tell him … Oh, that woggal big fellow; he makebilya/beelier (rivers), kata (hills), boorna (trees) everywhere … Noongar people said the woggal’s place of abode was to be avoided otherwise he would create vengeance upon anyone who disturbed him … Woggal lives in the sea, in the hills and rocks; but his favourite camping ground is the deep waterholes.”[v]

Nyungar believe in the Waakal very dearly. They reckon without the Waakal around they would have no water. They would not let the kids go and torment the Waakal. They would drive them away.

There is a Waakal in the Swan River and he very rarely shows himself. If the water was muddy, the old grannies used to say don’t swim in there, because he is having a feed. Don’t swim (warra wirrin, a bad spirit); wait until the water is clear then you can go and jump in (quop wirrin, a good spirit).

He was very important to their lives, because they believed in having fresh water. They wanted the water, so they wanted the snake to stay alive.

Noongar Elder Dorothy Winmar [vi]

The storylines, song-lines and Dreaming associated with the creation of all life form the basis of the Nyungar belief system (kundaam). This treading in the steps of our fathers reaffirms the beliefs, values, the social structures and fabric of the creation of the earth, the water and the sky and all things that live in and on it. [vii]

Noongar belief in the Waugal and its control over the fresh water is as relevant today as it has been since kura kura – long long ago.

Jirda – Birds

Noongar Words

djidi djidi – willy wagtail

darlmoorluk – twenty-eight parrot

weerlow – curlew

woodartjis – little people

bulyits – little “hairy” smelly people

Noongar people have a deep sense of understanding about the role that jirda (birds) play within our spirit world. Jirda are often messengers in Noongar boodja (country). Some of the birds include the weelow (curlew), djidi djidi (willy wagtail) and darlmoorluk (twenty-eight parrot). Weerlow is said to be the ‘bringer of death’; djidi djidi can take you into the bush to the gnardis or woodartjis and bulyits (little “hairy” people), and darlmoorluk is the ‘guardian or protector of the camps.’

Oh, Nyungar people feared him. If there was a place where they saw old Weerlow, they would never go there and camp, they would always camp away from him and if Weerlow lived in a certain area, they would turn their tent camps away from him. They would never put him between their camp and the fire. They would never ever go and camp near where there were Weerlows, even my mum and old Uncle Tom Bennell and them. They were very powerful birds and the old people would say, wherever he is, he is death or someone is going to die if you hear him. He was always the bringer of death. Yeah, he was a symbol of death.

Noongar Elder Janet Hayden [vii]

The djitti djitti was the little bird that lured you into the bush for the gnardis, the wudartjis. You’d always find that you’d never, ever go out of the circle of firelight, if we did go to the dark areas, that’s where the gnardis and woodartjis were. But during the day, the wudartjis were quite cunning, they’d actually hide in caves and behind rocks and they’d have this ability to blend in, so you can’t see them, but sometimes you could smell them. As a kid, you’d be told to watch out for the djitti djitti, because it will keep taking you away and even today you’d find that a djitti djitti, when you go to it, it doesn’t fly away. It will just bounce a little bit and entice you further and further away. It just keeps bouncing and before you know it, you’re way into the bush. So if you’re a child, you think you can catch it, ’cause it’s just in front and it’s bouncing around and it mesmerises you and before you know it, you’re way into the bush and you could be lost. That’s one of the first bird stories I actually heard – watch the djitti djittis ’cause he’s taking you to the wudartjis.

Dr Richard Walley [viii]

The Nyungar used to call it darlmoorluk or twenty-eight parrot, darlmoorluk, that’s it. Ha Ha, twenty-eight! He was a happy bird. If we knew he was coming to camp, he was not only a good feed, you know, Nyungars used to have a good feed out of that fella, but he was a happy bird. Sometimes the Nyungars only kill them when they were desperate. They always told the kids that this fella was good to have around. He was a protection at our camp, if you know that this fella, this darlmoorluk, was going, then you fellas don’t let your kids wander around because the woordarji, or the little bulyits, or whatever, yeah, or the djenagubbi is going to come around. Don’t let them run around, but if that darlmoorluk was there, you know that your camp was safe.

Noongar Elder Sealin Garlett [ix]

Spirituality and Sense of Place

The link between past and present continues, with stories that are unique to a place or community in Noongar boodja. Sacred places are special to us because we’ve been told a Dreaming story about that place by our mother or by our Elders.

We know what things have happened in this place, and we know if we are allowed to be there or not. Sometimes, you don’t know they are special places, until you come across them. You may have heard about it, but you don’t know until you get there. It can be still and quiet, and then suddenly a wind comes across the water, circles a tree in the middle. How eery and powerful that is. And you know straight away it’s a special place.

Carol Innes and Margaret Drayton, SWALSC, 2011

If you go camping enough you come across ’em. There’s plenty of sacred places. In the metro, there are so many traditional grounds where spirituality still lives. If you’re out in the bush at night; you might look across the river, and in a glance, see a bunch of full bloods around a fire having a corroboree. And then, just as quick, they’re gone.

Kevin Fitzgerald snr., oral history, SWALSC, 2011

We come here to this place, Minningup, the Collie River, to share the story of this area or what makes it so special. It is the resting place of the Ngangungudditj walgu, the hairy faced snake. Bardan ngang noyt. He is our spirit and this is where he rests. You have big bearded full moon at night time; you can see him, his spirit there, his beard resting on the water. And we come to this place here today to show respect to him plus also to meet our people because when they pass away, this is where we come to talk to them. Not to the cemetery where they are buried but here because their spirits are in this water. This is where all our spirits will end up here. Karla koorliny, we call it – coming home. Ngany kurt, ngany karla – our heart, our home.

Joe Northover, oral history, SWALSC, 2009

It was something taught to us by our mother and our older sister. So you knew the places you could go to that were safe, or that women were allowed to go. If we went to a swimming hole, we knew if it was all right. And even sometimes when you got there, you’d know it wasn’t safe. It was a feeling you had. It could be the time of day or the time of year.

My mother always said to us to trust your inner feelings. If it wasn’t right, didn’t feel right, we should just quietly leave. Don’t ask me how I know. It’s not something that can really be defined. But it’s a connection. A connection to land, country; to nature. Like if you’re Catholic, you believe in one person (a god), but for Noongars it’s a connection to place or country. I call that spiritual – that feeling, following your intuition.

Margaret Drayton, SWALSC, 2011

You need to be careful I guess … Well sometimes you can sense it yourself with a feeling you know you get a feeling that it’s not safe here, that you’ve got to back off. That’s if you’re in tune with if you’re in tune with the environment and things around you – … You’ll basically you’ve got to be able to tune into the country. and you’re more or less your senses will tell you then – . If you’re going into into country that’s dangerous …Well it’s hard to explain where it comes from but in your mind in your mind – . You start to get that feeling well this is not right you know I shouldn’t be here. I’m getting into dangerous country. It’s something that’s, it’s like a sixth sense that’s coming into you you know and it’s like I said it’s a matter of being tuned into a thing, into the environment and into the environment around you … Well basically, … it’s just just a sense. It’s a sense that that … you shouldn’t be there and you get very uncomfortable and if you stay there it sort of increases, and it’s like a voice saying to you, you’ve got to get out of here you know you shouldn’t you’ve got no right to be here …

Glen Colbung, oral history, SWALSC, 2009

There’s a lot of old people who have been through there(Wandering Mission) over the years and their spirits will come back to that place. Sometimes, we will talk about that ….. we won’t talk about that in the night time though. Yes, it had everything. Wandering had everything and there was sadness there, too. ….Yes, there was that too and there’s those old people who died who keep coming back to see their children. Their spirits keep coming back. A lot of children were there before I went there [with Joe Walley in the 1970s] ……Yeah, God only knows what happened before me and Joe got there.

Margaret Gentle [x]

Baronga – Totems

Noongar Words

yarkan – turtle

kwooyar – frog

yoorn/yoondarn – goanna

weitj – emu

kip – dolphin

maali – black swan

yongka – kangaroo

waalitj – eagle

Noongar spiritual obligations to our spirit ancestors are maintained according to the totems that live in our environment. Some examples of Noongar totems are jirda, birds, kwooyar – frogs, gooljak, kooljark, koolyak – swans, yoorn/yoondarn – goannas and karda/caarda- lizards. Every individual has a spirit totem or an animal which we have a responsibility for and must treat with respect. We do not eat the animal of our totem. Children are still given totem animals today to look after and preserve. It is part of maintaining our cultural traditions and a connection to all living things.

Our family totem on my grandfather’s side, Pop Tom Bennell and great Grandfather Doorum Bennell and that is the frog, in our Noongar language Kweeya, he is the Bennell frog. He is brown and has white marks on him. I heard the Bennell frog went around to some of our relatives houses in Brookton and they knew he was bringing them news that we had lost mum.

Sandra Harben, SWALSC, 2013

You’ll also find that in our area we had the totem like weitj; he was one of our totem eagles. We also had a totem, which was the kip, the dolphin, that was another totem for us and yonga, the kangaroo. You’ll always find that sometimes people say you got that totem, but one totem shows you who you are, and our major totem in the area was weitj and that we also had other totems, with different family connections. So where you’re from, the different locations and I think that trees and the plants are also parts of your totem.

Dr Richard Walley [xi]

Traditional Practices

Throwing of Sand

A river is a spirit home and we go there to visit our ancestors. We throw sand to let them smell us. When someone dies, we go there and sing them home.

When Noongar people visit a river or water body, we throw a handful of sand into the water. We use language to let the Waugal know of our presence. Noongar people see the condition of the rivers and waterways as directly related to the well being of the Waugal. It is part of our caring for country and the cultural landscape to ensure the Waugal is not disturbed. If the water body is disturbed, it means the Waugal is too. Failure to throw sand into the water could cause us harm in return. When we practice this custom the water can be safely used for swimming – djabooly-djabooly, drinking – djoriny, catching fish – gil-git or turtle – yakkan, yakkinn, ya-gyne.

Smoking Ceremony (Cleansing Ceremony)

The smoking ceremony is a traditional Noongar ritual used to not only cleanse and purify a specific area but it cleanses the spirit, body and soul whilst you are on Noongar Country. It also helps to ward off warra wirrin – bad spirits and to bring in the blessings of the kwop wirrin – good spirits.

The leaves and shavings from the balga (grass tree) smolder and the smoke purifies the area and prepares for a new beginning. This ritual of purification and unity – signifies the beginning of something new.

The balga tree is the life tree. It provides medicine, food, shelter warmth and healing.

The Smoking Ceremony is a blessing while you are here on Noongar Country, to keep you safe. Smoking ceremonies can be used in Welcome to Country and before camping in a new area.

Welcome to Country

Welcome to Country ceremony is an acknowledgement and recognition of the rights of Noongar peoples traditional country. This acknowledgement pays respect to the traditional custodians, ancestors and continuing cultural, spiritual and religious practices of Noongar people. Further it provides an increasing awareness and recognition of Australia’s Aboriginal peoples and cultures. The Welcome to Country is an acknowledgement and recognition of the rights of Noongar people. The act of getting a representative who has traditional local links to a particular place, area or region, is an acknowledgement of respect for traditional owners. It is respect for people, respects for rights and respect for country. The land, waterways and cultural significance sites are still very important to Noongar people. It is an acknowledgement of the past and provides a safe passage for visitors and a mark of respect.

Welcome to Country by Noongar Elder Ms Marie Taylor. Courtesy City of Canning

Protocols are the standards of behaviour that people use to show respect to each other. Every culture has different ways of communicating, and in order to be able to work with someone from a different culture in a respectful way you need to understand how people from that culture communicate.

The following Welcome to Country was written by Noongar Elders for the Commonwealth Festival Program Perth, Western Australia in 2011.

Ngalluk jurapiny wanju nunnuk

ngallah Noongar Boodja

Nitjah ngallah moorts Boodja

koorah koorah

Nitjah ngallah karllah Boodja

koorah waanginy gaany ngallah

jurapiny moort ngallah boodja

Koorah waanginy kedala,

Ngallah yaakingy ngallak Noongar

NyitiyangNgallak, Ngallak-a gaany

(Translation)

We are pleased to welcome you to our Noongar country

This is our ancestor’s land from the dreamtime

This is our homeland of history

And as one we are proud people of our land

Through history till today, we stand together black and white

We are, we are one

Written by Noongar Elders Doolan-Leisha Eatts, Yuraleen Dorothy Winmar and Frederick Joseph Pickett

Ngallak Koort Boodja Group members

Welcome to Country guidelines and protocols.

References

[i] Winmar, Ralph (Munyari). 1996. Walwalinj the Hill that Cries. Nyungar Language and Culture. Perth: Dorothy Winmar in Sandra Harben, ‘Literature review for Avon Basin Noongar heritage and cultural significance of natural resources,’ Perth: Murdoch University, 2005

[ii] Bennell, Tom. 1978 b. Oral Interview. Transcribed in 2002 in Harben, ‘Literature review for Avon Basin Noongar heritage and cultural significance of natural resources,’ 2005

[iii] Winmar, Ralph (Munyari). 1996. Walwalinj the Hill that Cries. Nyungar Language and Culture. Perth: Dorothy Winmar in Harben, ‘Literature review for Avon Basin Noongar heritage and cultural significance of natural resources,’ 2005

[iv] Harben, ‘Literature review for Avon Basin Noongar heritage and cultural significance of natural resources,’ 2005

[v] Bates, Daisy. 1992. Aboriginal Perth Bibbulmun Biographies and Legends. P.J. Bridge. ed. Victoria Park, WA: Hesperian Press.

[vi] Winmar, Dorothy. 2002. Oral Interview. Transcribed in 2002 in Len Collard, Sandra Harben and Rosemary van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy: A Nyungar Interpretive History of the Use of Boodjar (Country) in the Vicinity of Murdoch University,’ Project Report for Murdoch University, 2004, http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/multimedia/nyungar/info/project.htm

[vii] Wheatbelt Natural Resource Management, Nyungar Budjara Wangany: Nyungar NRM Wordlist and Language Collection Booklet of the Avon Catchment Region, 2009

[viii] Hayden, Janet. 2002. Oral Interview. Transcribed in 2002 in Collard, Harben and van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy,’ Project Report for Murdoch University, 2004, http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/multimedia/nyungar/info/project.htm

[ix] Walley, Richard. 2002. Oral Interview. Transcribed in 2002 in Collard, Harben and van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy,’ Project Report for Murdoch University, 2004, http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/multimedia/nyungar/info/project.htm

[x] Garlett, Sealin. 2002. Oral Interview. Transcribed in 2002 in Collard, Harben and van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy,’ Project Report for Murdoch University, 2004, http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/multimedia/nyungar/info/project.htm

[xi] Gentle, Margaret. 2002. Oral Interview. Transcribed in 2002 in Collard, Harben and van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy,’ Project Report for Murdoch University, 2004, http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/multimedia/nyungar/info/project.htm

[xii] Walley, Richard. 2002. Oral Interview. Transcribed in 2002 in Collard, Harben and van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy,’ Project Report for Murdoch University, 2004, http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/multimedia/nyungar/info/project.htm