Food

Noongar Words

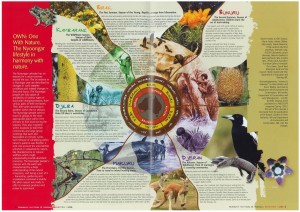

Seasons:

Birak – December and January, the first summer

Bunuru – February and March, the second summer

Djeran – April and May, autumn

Makuru – June and July, the first rains

Djilba – August and September, the second rains

Kambarang – October and November, the wildflower season

Food:

bardi – witchetty grub

yongka – kangaroo

karda – goanna

djildjit – fish

wardan noorn – eel

yarkan – turtle

yurenburt – berries

yoorna – bobtail lizard

Noongar Seasons

Noongar people have traditionally hunted and gathered food according to the six seasons. In our Noongar language these are called Bunuru, Djeran, Makuru, Djilba, Kambarang and Birak and are determined by the weather patterns. The seasons tell us which animal and plant resources are plentiful at those times. Noongar people know when it is the season for harvesting by signs in nature. A hazy summer sky foretells of the salmon running or the blossom on paperbarks brings the mullet fish. Noongar communities have always taken care to assure the survival of animal and plant species. We always leave some honey for the bees to build on. And when the fish travel upstream to lay their eggs, we catch them on their way back down.

For Noongar people, the bush is our gourmet delicatessen. We harvest many types of yurenburt (berries), karda (goanna), bardi (witchetty grubs), yongka (kangaroo), turtles, and birds’ eggs. Food from the sea and waterways are a major resource for Noongars: djildjit (fish), wardan noorn (eel), abalone, cobbler, marron and gilgies.[i] Fishing was traditionally carried out by men, whilst women gathered yams, berries, and quandongs.

It is an important part of Noongar custom and lore to take only what you need from nature in order to maintain biodiversity.[ii] By eating foods when they are abundant and in season, natural resources are not depleted and will still be available for the next year. As guardians of our country, we achieved balance and adaptability through thousands of years of living in harmony with the bush. Our knowledge of the seasons and managing the land was given to us by the Waugal and passed down by our Elders.

Tools

kodja – axe

mullers – flat grinding stone

In order to hunt and gather food, Noongar people made stone tools and used different shaped tools for specific purposes. Stones that we shaped like axes, we call kodja. These were attached to a wooden handle for chopping and shaping wooden objects.[iii] Small, slender blades were used for cutting and slicing. Some tools were attached to spears using resin or yongka (kangaroo) sinews to create a handle, making the tool easier to use. To make flour, we would grind acacia seeds with a round stone that fitted neatly into our hands. The flat stones we call mullers would be worn smooth by grinding.

Moort and Merenj in our Boodja (Family and Food)

moort – family

dartj/daadja –meat

merenj – food

boodja – country

weitj – emu

maam – man, men

yorga, yok – woman/women

koolangka – children

nyingarn – echidna

goomal/ngwir – possum

kooyar/kwiyar -frog

kaarla – fire

gilgie – freshwater crayfish

Wattle should be out soon. When that wattle come out you know it’s a good time to go bush. Djerung. Fat. All fat and djerung.

Joe Northover, oral history, SWALSC, 2008

The Jetta family from Kellerberrin talk about kaarda – the lizard and what it meant to them.

Noongar people have moved around our moort boodja (family run) for thousands of years to find food. Hunting for dartj/daadja (meat) was a daily activity carried out by the men. Noongar maam (men) hunted large animals like the yongka (kangaroo) and weitj (emu) and wild duck. The yorga or yok (women) and koolangka (children) would gather smaller animals such as the nyingarn (echidna), karda (lizard) and goomal/ngwir (possum).

Some of the food collected by yok also included kooyar/kwiyar (frog), gilgie (freshwater crayfish) and yarkan (turtle). Women had the expertise for finding and catching freshwater yarkan (turtle) in the dried-up swamps, pools and other waterways. They would wade through the water using their toes to detect the breathing holes where turtles, gilgie and frogs were found.

A Noongar would have said to his moort when they were around their karla, do you want to dartcha koorliny? That means do you want to go hunting for meat or merinj koorl buranginy – go looking for vegetables.

Noongar Elder Tom Bennell in Collard, Harben and van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy’, 2004

‘I stood in the midst of a large plain, which they had surrounded on three sides, multitudes of kangaroos – I believe I might say thousands, came rushing past me.’ (Early colonial account of a Noongar kangaroo hunt 60 miles south of York in Western Australia.) [iv]

Noongar Elder, Dr Rosemary van den Berg writes: ‘they hunted kangaroo (yongka), emu, (waitj), possums (coomarl), snakes, (land snakes, not water snakes), lizards (caarda, and yoorna), turtles and their eggs, honey, birds like rosellas, bronze-wing pigeons, ducks and their eggs and the bardi grubs, which could be eaten raw or cooked in the coals. Their vegetable and fruit intake included edible tubers, quandong, berries and nuts and a type of grain which could be crushed and made into a damper. The boyoo or toxic zamia palm had special treatment before it could be eaten.’[v]

[I] couldn’t believe how big their nests was and how far down we had to dig…When we got to the egg you could see them all circles where they laid and they’d [the Elders] say, make sure and leave three or four there and they’d only take a couple … so that when the hen came back she would see where the eggs are.

Peter Farmer snr., oral history, SWALSC, 2011

Flora and Fauna Resources

koorndie – large stone

quardiny – wild carrot

boyoo – zamia palm

bookas – cloaks

chootas – bags

We don’t waste any part of an animal that is killed or plants that are gathered: everything is useful. Nearly all of a kangaroo can be used – from the meat for eating, to the skin for making booka (cloaks), and sinew for stone tool hafting. The balga bush (grasstree) has as many as 28 different uses, some of which are medicinal.[vi]

But with the kangaroo, that was probably one of the most important things to the Noongars because they used to use the skin. Like I said, they used to skin the kangaroo and either peg it to a tree or just peg it down along the ground with the fur down and the skin up. And once it dried off they used to get a [broken] bottle and just you know, all the bits of – oh, didn’t look too good so they’d scrape it all off… They used to scrape the kangaroo skin like that.

Peter Farmer snr, oral history, SWALSC, 2011

In the past Noongar used the long green parts of the bush for their mia mia to shelter them from the weather … Noongar also used the balga bush for merenj (food), they used to dig down to the white shoots, which can be found at the bottom of the grass. Even today the balga bush is important to Noongar for lighting fires, whether it is in their homes or when they go out to the bush … As you can see, the balga bush provides many uses for the Noongar and this is why I like to paint them.

Donna Rioli, pers. communication, 2008

Traditional clothing consisted of bookas (cloaks) and chootas (bags) made from kangaroo skins and fastened with bone. Ceremonial head dresses were adorned with emu or cockatoo feathers, and fur from animals, such as the possum. Ochre was used for decorating the body for ceremonial or important occasions.

Devil’s Lair and Long Ago

Noongar people have a long and continuing connection to many sites of significance. Devil’s Lair cave in Margaret River is one such place where Noongar people lived. Archaeological evidence of our ancestors dates back about 48,000 years and excavations have uncovered stone artefacts, animal bones, hearths and bone artefacts. The bones of animals and remains of plants tell us what people used to eat, and how what they ate changed as the environment changed.[vii] The changes in climate and the environment over long periods have made Noongar people adaptable to different landscapes. In the last 30,000 years the vegetation and climate of the south-west has changed dramatically: from a dry, cold environment with few resources to a gradually warming climate with large forests. The site of Devil’s Lair [below] shows evidence of the sorts of foods eaten by Noongar people, from the bones of small animals and remains of plants, along with stone tools and ashes.[viii]

Changes in Noongar Food as a Result of Colonisation

As Noongar land became more populated by Europeans and their stock, conflict arose over access to country. Noongar people stayed on country but went to work for farmers, keeping traditional Noongar ways but accommodating new European ones. Noongar workers were not paid much, and often, not at all. This is known as Stolen Wages. The lack of wages, along with disruption to our traditional practices, resulted in Noongar people having to rely on rations, such as tea, sugar and flour.[ix] Noongar people made do with what was available, existing on thin stews, lamb’s tail and rabbit. We also gathered whatever bush foods we could; these would supplement any rations with low nutritional value. Children on missions had little choice but to make do with the often insufficient food that was served, such as porridge and watery stews.[x] Often, Noongar children would seek out bush foods, like karda (goanna) or berries, as a way of supplementing their poor diet.

Doolann Leisha Eatts talks about hunting and gathering

Elder Doolann Leisha Eatts talks about hunting and gathering

Audio Transcript

Chris Owen: What were they eating or how were they living if they weren’t being paid or they were being shifted off the land?

Doolann Leisha Eatts: Well lot of ’em it was good that they you know, went hunting. There was lots of kangaroos around. They lived off the land in lots of ways, you know they went kangaroo hunting, and they ‘ad guns and they ‘ad kangaroo dogs as well. That’s good they brought the rabbits out ’cause the rabbits breed like flies. And another thing that they lived on was rabbits.

Chris Owen: Yeah, yeah.

Belinda Faulkner: So how would they cook those?

Doolann Leisha Eatts: Oh they cooked it in the ashes, they cooked their dampers in the ashes or they cooked it in the camp oven. You know they’d ‘ave a change, they’d cook the kangaroo tails in the ashes with the skin on, sometimes they’d skin it and make a stew in the oven. And they done the same with the kangaroo meat itself. And the rabbits as well. They used to go and get the honey trees, look for the ‘oney trees and you know go and chop the tree down and get the honey out. And leave some ‘oney of course for the bees to build onto. And so they had their honey off the land and they had — they used to pick the quandong nuts in its seasons and make jam and make their pies and that, you know. But they just barely lived. A good meal was a luxury for them.

From: Doolann Leisha Eatts interview for South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council, 17 January 2007

Disclaimer

SWALSC followed cultural protocols to obtain permission to use this oral history on the Kaartdijin Noongar website.

It is also protected by copyright law and may only be used for private study, research, criticism or review. If you would like to use it for any other purpose, including publication, making copies or modifying it, please contact SWALSC at reception@noongar.org.au or PO Box 585, Cannington, 6987.

Note: In some cases the written transcript has been edited with permission from the person interviewed and may differ slightly from the audio recording.

Permission to use this audio recording kindly granted by Elder Doolann Leisha Eatts

Hazel talks about what foods were available growing up

Kayang (Hazel) Brown talks about what foods were available growing up

Audio Transcript

Hazel Brown: You know, they sort of, when Aboriginal Affairs Department was government, it was moving, moving, all the time moving. And not unless you went on to a farm and you went to stay on a farm and then the farmer got in touch with Aboriginal Affairs Department and the Native Affairs and that they was employing you. And you were allowed to stay there then. But apart from that, you just moved, you know. When we stayed at Needilup if we … if we didn’t have any food, well Dad used to go down to Sparks and he did dingo trapping but mostly he used to snare kangaroos and shoot kangaroos and sold the skin and they’d go and ring up to Pop Hassell and said that we were short of food, we needed flour, tea and sugar. And then Pop would come on a horse, you know, he’d have to start early and he’d come down, Eddy Hassell, he’d come there sometime. He did bring a pack horse and about 25 of flour and then sugar and tea and then Nestles milk. And sometimes he bring fat in tins, jam and whatever. And of course, ginger bread biscuits.

From: Kayang (Hazel) Brown, Interview for South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council, 18 June 2008

Protocols

SWALSC followed cultural protocols to obtain permission to use this oral history on the website. It is also protected by copyright law and may only be used for private study, research, criticism or review. If you would like to use it for any commercial purposes, including publication, making copies for sale, or modifying it please contact SWALSC on reception@noongar.org.au or PO Box 585, Cannington, 6987.

Note: In some cases the written transcript has been edited with permission from the person interviewed and may differ slightly from the audio recording.

Permission to use this audio recording kindly granted by Kayang (Hazel) Brown

Martha Borinelli – Eating bush food as a child

Martha Borinelli talks about going out and eating bush food when she was at New Norcia

Audio Transcript

Henry Cox: Did they let you do that? Did they know you were doing that?

Martha Borinelli: No, we just went in the bush and did it ourselves on a picnic or on a walk, you know. And … and because that was part of our Aboriginal tradition, you know, and we were … then we go down there and get some jilgies or something like that or go and get, you know, kangaroo berries off the bush and have, you know, these beautiful berries, you know. That was our tucker and we thoroughly enjoyed it because that’s what we grew up with. And the turtles, you know, we’d have a turtle, we’d all sit down there and start eating, you know, and having a good old feed. So that was kept … that kept us, I think, kept our tradition going and knowing that we are Aboriginals, you know, that we are Noongars and very strong, that’s a very strong connection when you know that you … you’ve got that background of what your ancestors taught you, you know, your grandparents and your parents and the bush tucker they showed you how to make and all that and we’d make our own damper and just chucked it in the fire because that’s what we … we knew what to do, you know. So that’s what kept us going.

From: Martha Borinelli, nee Taylor, interview for South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council, 15 May 2007

Protocols

SWALSC followed cultural protocols to obtain permission to use this oral history on the website. It is also protected by copyright law and may only be used for private study, research, criticism or review. If you would like to use it for any commercial purposes, including publication, making copies for sale, or modifying it please contact SWALSC on reception@noongar.org.au or PO Box 585, Cannington, 6987.

Note: In some cases the written transcript has been edited with permission from the person interviewed and may differ slightly from the audio recording.

Permission to use this audio recording kindly granted by Carina Ward, Mark Borinelli, Sergio Borinelli and Andrew Borinelli

Sharing and Food Today

Sharing what you have with family and friends is a constant of Noongar life and it especially applies to food. It doesn’t matter what you have to give, it is the sentiment that counts. If we haven’t seen people in a while, or if they are visiting from far away, we share what food we have, whether it be a little or a lot, to celebrate being together.

‘If we got a kangaroo, you know we’d share it up with all our family and some. If we knew some people had nothing we’d give them some. The same with the sheep, you’d share that up too.‘

Peter Farmer snr., oral history, SWALSC

Food can be seen as a way of reconnecting with our Noongar identity and family ties. Today, it can still be an activity to do when out on country – hunting, gathering and caring for country. Noongar people still fish and hunt for gilgie or a yongka (kangaroo). Importantly, the traditional knowledge and ways of collecting food continue – which season to gather specific resources, where to find food and how to prepare it.[xi] Today, more than ever, the concept of caring for country is important as more pressures are placed on the land. This means caring for plant and animal resources so that they will be healthy and abundant in years to come.[xii]

My sister Fanny and me always look for the honey trees and you know, go and chop the tree down and get the honey out. And leave some honey of course for the bees to build on to. And so we had our honey off the land.

Doolann Leisha Eatts, oral history, SWALSC

References

[i] Kawalilak, R. (ed), ‘Hunters and Gatherers‘, Conservation and Land Management Booklet, 1998 (Reprint from Landscope Magazine, Spring 1992)

[ii] Stranger, R., ‘The Avifaunal Prey of the Perth and Mandurah Aborigines’, 2005

[iii] Lourandos, H., ‘Continent of Hunter Gatherers‘, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997, p. 292

[iv] Landor, E. W., The Bushman; or, life in a new country. London, Richard Bentley, 1847 in Hallam S., Fire and Hearth:a study of Aboriginal usage and European usurpation in south-western Australia. Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1975 p.36

[v] Collard,L, Harben, S & van den Berg, R., ‘Nidja Beeliar Boojdar Boonookurt Nyininy: A Nyungar Interpretive History of the use of Boodjar in the Vicinity of Murdoch University’, 2004

[vi] Kawalilak, R (ed), ‘Hunters and Gatherers‘, Conservation and Land Management Booklet, 1998 (Reprint from Landscope Magazine, Spring 1992)

[vii] Lourandos, H., ‘Continent of Hunter Gatherers‘, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997, p. 198

[viii] Lourandos, H., ‘Continent of Hunter Gatherers‘, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997, p. 199

[ix] S. Hallam, Fire and Hearth: a study of Aboriginal usage and European usurpation in south-western Australia, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1975

[x] A. Haebich, Broken Circles, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 2000, p.234

[xi] A. Haebich, Broken Circles, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 2000, p.388

[xii] Kevin Fitzgerald, pers. comm., 15 February 2011