Identity

The Aboriginal peoples of Australia have the oldest continous living cultures in the world.

WAAETC, Western Australian Strategic Plane for Aboriginal Education and Training 2011-2015

Noongar Words

boodja – country

moort – family/relations

kaartdijin – knowledge

wedjela – (slang for white person) non-Aboriginal person

By identity we mean ‘who we are.’ A part of the right of any group to self-determination is the right to say for themselves who they are and what defines their identity according to their own understandings.

To be Noongar is to belong; it is to have connection to our boodja – country, our moort – family, and to kaartdijin – knowledge. To be Noongar is to be a river person or a coastal person or just from the bush. It is to have pride and to survive. We need to celebrate it – the journey.

Ask a Noongar person what our identity means to us and invariably we will talk about the stories. The stories are part of the kaartdijin passed down from the Elders and moort (family). They tell of how to survive in the bush. They are campfire stories of the stars and the seasons. How a change in the ants’ activities can tell what will happen in one week or two. And when it’s time to go bush and look for the bush foods in season.

Since colonisation, for the better part of 200 years, Noongar have been trying to regain some of the freedom, some dignity, some sort of peace in a world that is irreversibly different from that which came before it. At the same time though, there are many Noongar people who have remained strong, who have been carriers and custodians of our culture and language, carers of our country, backbones of our families and advocates of our people.

Glen Kelly, Chief Executive Officer, SWALSC, 2011

The Noongar community is bound by strong common bonds, based on our shared culture, language, connection to country and common ancestry. Our identity is expressed through stories and storytelling, through song, dance and music. It is also expressed through sport and community. Whilst there are common elements of Noongar identity, there are also different perspectives of what identity means.

My first memory’s that I am Nyungah and I am Aboriginal and that there are white people out there and some of them don’t like us.

And sittin’ round the campfire with my grandmother, my aunties, my uncles, my mum, my dad, and they tellin’ us dreamtime stories. At night, again and again they used to tell us ghostly stories, they used to show us the stars, and talk about the stars, ’bout the seasons, they tell us about the birds, the ants, the behaviour of them and how the seasons change…

Doolann Leisha Eatts, oral history, SWALSC, 2003

Well, I was, I always knew since I was, I guess, old enough to think I was a Noongar. You know, and I say ‘Noongar’ not Nyungah like some people say. I dunno whether that’s the right word but we’ve always used Noongar. That’s our, whether it’s our skin colour or just being part of the Ballardong clan I suppose.

Kevin Fitzgerald snr., oral history, SWALSC, 2011

Country and Identity

Noongar people believe that land is an inseparable part of our identity, and a significant part of being Noongar is to care for country. A Noongar person’s sense of connection to country is influenced by our affiliation with a place, with our family, and our obligations to the land and all things in it.

Glen Colbung talks about returning to country:

They come back to their traditional country yeah… Well, that’s part of you know, part of Noongar culture. A very strong part of it is that you know where your roots are and you come back. The thing with my particular family is that we’ve never moved away from the Mount Barker, Albany region. We’ve always been there.

Glen Colbung, oral history, SWALSC, 2011

Moort – Family

Noongar identity is strongly linked to family. The fundamental building block of our community and culture is our family. Elders are important in the extended family, as they are the keepers of kaartdijin. Elders command respect in our communities, and are recognised for their vast knowledge of culture, country, lore and community.

Kayang Hazel Brown talks about growing up Noongar, being taught by her family:

I was taught about the lore and traditions of the people of our region by my parents and elders. Our people were mostly kept together by Henry Dongup and Waibong Moses. I grew up with my brothers and sisters among our father’s full blood relations. When we were young we always kept the lore of our people who were traditional people.

We mostly lived in bag camps – you know, like tents made of old hessian bags and canvas and that – and we slept on rushes or bushes for our beds. We ate the bush food of our people too.

Kayang Hazel Brown, oral history, SWALSC, 2008

Culture and Identity

Identity is maintained through our close relationships to family, community and country. It is affirmed through our culture and the expression of language, dance, music, and importantly, stories. Stories are passed on through the Elders. The stories represent our belief systems and our knowledge of country.

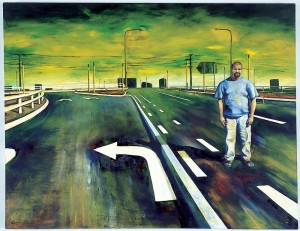

The painting’ Nyoongar Dreaming’ is a perspective on Noongar identity in a changed world. For more information see Art Gallery of WA.

Christopher Pease, ‘Nyoongar Dreaming’, 1999, oil on canvas. State Art Collection, Art Gallery of Western Australia, purchased 2001. Permission of the artist.

Corroboree: Dancers include Noongars Joobaitch, Monop, Dool and Gen-burdong, and Pompey and Wab-bing from Southern Cross and Broome. Courtesy State Library of Western Australia, The Battye Library 009489PD

Noongar Sport, the Arts and Politics

NOONGAR WAN-A. The young Noongar girls in the southwest of Western Australia played many skill games. In one of these a short stick was placed on the ground and the other girls attempted to hit the stick while the girl defended it using her wana (digging stick). A wana is a digging stick in the Noongar language of the south-west of Western Australia. This game is named for the Aboriginal people who played it. Different versions of this game have been recorded by observers.

Australian Government, Australian Sports Commission

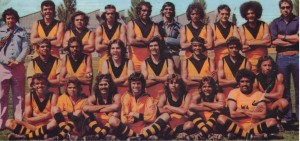

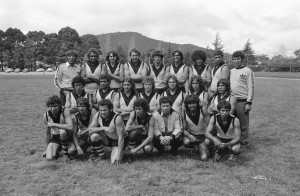

Many Noongar people have participated in sports at all levels. In the 1970’s the Federal Government set up the National Aboriginal Sports Foundation and the first State Aboriginal Football and Netball teams were selected to participate in a National carnival held in Canberra.

WA State Aboriginal football team, Canberra 1974.

Courtesy National Archives of Australia: A8771, 741006/103

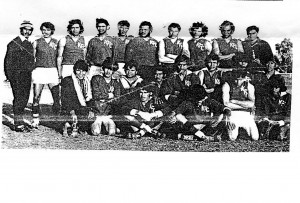

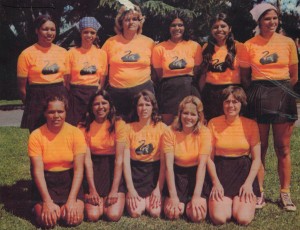

The National Aboriginal carnivals continued and were held in Tasmania in 1975, Alice Springs in 1976 and Adelaide in 1977.

Western Australian State (Aboriginal) Netball Team, Tasmania 1975. Back row: Gillian Collard, Geraldine Hayden, Ivy Bennell (Coach) Debbie Thorne, Jenny Bonney, Dorothy Henry

Front row: Vicki McHenry, Charmaine Slater, Betty Collard, Sandra Collard, Ollie Brown. Courtesy Geraldine Hayden

Other Noongar people have achieved high repute as professional football players, such as Graham ‘Polly’ Farmer, Phillip and Jim Krakouer, and in earlier years, the Wanderers football team from New Norcia. In the Arts we have artists Christopher Pease, Graham Farmer, Revel Cooper, Shane Pickett, Lance Chadd, Athol Farmer and Laurel Nannup; and writer, Kim Scott.

Wanderers football team, New Norcia, 1913. The group includes William (Billy) Wyatt and Alex Narrier – the two tallest men in the back row. In the front row sitting down from left: William Headland, Frank Narrier, and Melchoir Taylor, with Tom Narrier on the far right of that row. Courtesy Gus Ryder

Find out more about the Wanderers team in this 1949 newspaper article:

Wanderers football team in Western Mail, 28 July 1949, p.17

The “Kellerberrin Hayden team” were the first full Noongar team to play football in the 1960’s to play around the Great Southern area.

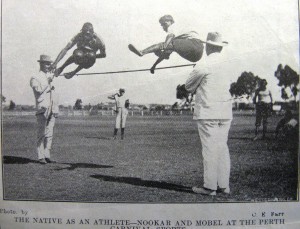

Noongar high jumpers Nookar and Mobel at the Perth Sports Carnival 1910. Daisy Bates collection, National Library of Australia MS 365 94/79

One third of Aboriginal AFL players are Noongar.

Sport can be a way of finding community and belonging. Sometimes it can overcome long held prejudices and reaffirm our identity. Martha Borinelli tells of her longing for acceptance in her town of Moora. When she organised a darts team, they joined the local club and won every year!

Martha Borinelli talks about setting up an Aboriginal dart team

Martha Borinelli talks about setting up an Aboriginal darts team

Audio Transcript

But if you are a strong person and you keep fighting all your life for what you want, you fight, fight and it’s very hard, you know, because sometimes people will never let you forget who you are and they wouldn’t ever let you have a go because I tried my hardest to be a good citizen in Moora but they still let me know that I was an Aboriginal and that I … my place wasn’t to be allowed to be there because I’m an Aboriginal and I just said to her well I’m just as good as you, as a matter of fact I might be a bit better than you, if you look at your own selves in the mirror. I said just because my skin’s a bit blacker doesn’t mean to say I’m any good.

So yeah, I told a few people that in Moora, I had lots of arguments with them, you know, I said Aboriginal people, we’re nice people if you want to let us have a go and give us a go and … and so how it come about, they were like, they’re very, very, very racist in Moora, then I said to the ladies, I said come on, let’s do something for this town, you know, we’re not going to let them get away with it. Let’s show that we’re just as good as they are. So we went and joined the dart club, the darts competition, Aboriginal people, we got our own dart team and won every year. And … and so we were allowed to go into this club then because we were dart players, you know, before they wouldn’t let us in.

Copyright: SWALSC followed cultural protocols to obtain permission to use this oral history on the Kaartdijin Noongar website www.noongarculture.org.au. It is also protected by copyright law and may only be used for private study, research, criticism or review. If you would like to use it for any other purpose, including publication, making copies or modifying it, please contact SWALSC at reception@noongar.org.au or PO Box 585, Cannington, 6987.

From: Martha Borinelli interview for South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council, 15 May 2007

Impacts on Identity

Despite the impact of Europeans and government policies aimed at destroying our Noongar identity, our identity and culture remains strong. Language is being taught in Noongar schools and in some non-Aboriginal schools. Places like the Wardan Centre in Yallingup bring Noongar culture to children and adults. Resistance to policies and the laws that have tried to oppress us have reinforced our Noongar identity. See Coolbaroo League.

Soup kitchen, Carrolup, 1915. Courtesy State Library of Western Australia, The Battye Library 003214D

Legislation on Identity

Noongar people have been racially classed under legislation almost since Europeans first arrived in Western Australia in 1829. Prior to 1972, there were at least 67 different categorisations about what it was to be an Aboriginal person in legislation on the basis of race, blood and caste. These racist categories bear no relationship to Noongar society or to who we are as people. Yet, these categories defined government policies and affected entire generations of Noongar families.

The Native Administration Act 1936, for example, created the classification of ‘quadroon’ (one quarter Aboriginal blood). However, a person of one quarter Aboriginal blood was not subject to the legislation if they were under 21 years of age and ‘did not associate and live in the manner of natives’.

Under the assimilation policy, from 1933 until the early 1970s, Noongar people who were deemed to fall under this category were removed from their parents and families and taken to institutions like Sister Kate’s Home in Queens Park. This resulted in what is known as the Stolen Generations. The paler your skin was, the more chance there was of you being taken. Often, children who were taken away were not told they had living relatives or even that they were Noongar.

Kevin Fitzgerald snr. tells how long it can take to find your identity:

Some people didn’t know their Noongar family. They had no idea of their background. They found out through photos or their wives getting together with other women and talking. They’d be having a cup of coffee and looking at the photos on the side table. ‘Hey, my husband’s got that same photo!’

That was how I found my cousin Des. His mother had married a wadjela (non-Aboriginal) and he and his siblings were brought up differently. He didn’t know where his family were from. Now his children are asking about their Noongar family. These are 30 and 40-year-old women wanting to know where they come from.

Kevin Fitzgerald snr., oral history, SWALSC 2011

The 1936 Act also stated that a ‘non-native’ could be classified as a ‘native’ by a magistrate. In the Native Welfare Act 1954, an Aboriginal person could be exempted from the Act if they served in the Armed Forces. These policies set up categories that relegated some Noongar families to reserves and others to missions or a combination of both. Some Noongar people escaped by working for farmers and living in the bush. As a consequence of this, people have different experiences of what it is to be Noongar person.

Margaret Drayton lived at New Norcia mission for a time; she talks about what life was like on missions and reserves:

We had access to some education living at New Norcia mission. Although, this brought its own restrictions, as we were bound to live by the mission’s rules and religion and were not allowed to speak our language. I have a strong connection to Yued country, around New Norcia. I take my children there to remember where they came from.

Margaret Drayton, oral history, SWALSC, 2011

Noongar people lived under severe restrictions whether on missions or reserves. This included not being allowed in towns at certain times (we could be arrested if found there after 6pm) or having limited access to services. See the Prohibited Area Map. Noongar people mostly weren’t allowed to drink alcohol, unless we had citizenship. But even citizenship brought with it restrictions on our freedom and identity. Those who had some access to towns had to go to a window at the back of the pub where ‘blacks’ were served, and then you could get one bottle of beer.

I remember as a little girl maybe about four or five years of age. I was walking in town (Brookton) with my pop Tom Bennell. He stopped at a window at the local pub, but it wasn’t made of glass it was like a boarded window.

He stopped and knocked on this window and it slid open and Pop asked for a bottle of beer, it was handed to him while we stood on the footpath. I have never forgotten that, now I know why this happened.

Sandra Harben, SWALSC, 2013

A lot of people didn’t bother with dog licenses, dog tags, that’s what we called em.

Kevin Fitzgerald snr., oral history, SWALSC, 2011

Despite restrictions and conditions, laws and policies, Noongar people have found ways to deal with the impact of colonisation. We have, in spite of everything, still maintained our cultural identity.

Martha Borinelli talks about escaping the mission to go bush. How she and her friends would catch a karda (goanna) and cook it over the fire.

You can find out more about Noongar identity in Kayang and Me, written by Noongar elder Kayang Hazel Brown and Noongar author and academic, Kim Scott.