Coolbaroo League

The Coolbaroo League was seen as a haven of hope when it began in 1947. It existed in a time of harsh restrictions for Noongars and all Aboriginal people, when we were not allowed to enter the central city of Perth. This barred Noongars from social venues and clubs when everyone else went out dancing of a Friday night. So a dance club of our own was formed, outside the restricted area. It provided a safe place for Noongar and other Aboriginal people to be ourselves, away from the persistent presence of the police.

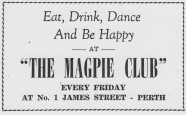

Coolbaroo comes from the Yamatji word for magpie – a reference to reconciliation – with its colours of black and white. The Noongar word is koorlbardi. References to black and white resonated in different ways. Helena Murphy (nee Clarke), a founding member, saw it as representing identity and people of mixed ancestry; while others felt it expressed a desire for collaboration and change. The Coolbaroo League became part of a wider movement for Aboriginal rights. It raised awareness of issues affecting Aboriginal people, including the restricted entry for Noongar into the inner city. The prohibited area was finally abandoned in 1954, when the club was allowed to hold a ball at the Perth Town Hall.

Founding Members

The Coolbaroo League was founded by the young activist, Helena Clarke from Port Hedland, Yamatji brothers Jack and Bill Poland, and their wadjela friend, Geoff Harcus. The three young men had fought together in WW11, and they, along with Helena, were deeply concerned by the lack of recognition for returned Aboriginal soldiers and the discrimination in general against Aboriginal people. Along with two white activists, the McEntyre sisters, they organized the first Coolbaroo Club dance. Elders, Thomas Bropho and William Bodney were also politically active at the time and involved with the League from the early stages. With their influence, the dances took off and attracted a wide group of Noongar.

We wanted a little place where we could prove we could handle our own affairs.

Helena Murphy nee Clarke

in Haebich, Spinning the Dream

The founding members had all met at various stages on the Esplanade in Perth, which acted as a forum at the time, where Noongar and other Aboriginal people (as well as other activists) gathered to express their political views. What the founding members and a whole bunch of Noongar had in common was strong opposition to the inequality and oppression of Aboriginal people.

Ronnie Kickett in the Coolbaroo League art shop, 1955. Permission Roma Loo. Courtesy Stephen Kinnane collection

Well my father [Bill Bodney] was involved in later years, around about the 1940s, setting up the Coolbaroo League in Perth

Corrie Bodney, oral history, SWALSC

The Coolbaroo League had ‘big dreams right from the start’, according to Helena Clarke.[i] It had a distinct political agenda, and organized deputations to Ministers. It also founded the first Aboriginal newspaper, ran a youth group, as well as organizing the dances in East Perth and country areas, and set-up the Coolbaroo Aboriginal shop of souvenirs and art – the first Noongar business in the city.

League Aims

- To break down barriers and segregation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities

- Voting rights for Aboriginal people through automatic citizenship

- Scrap prohibited area laws

- The rejection of the assimilation model of ‘staged’ citizenship rights

- A housing project

- To raise living standards for Aboriginal people

- Young people to take pride in being Aboriginal

- Aboriginal control of League – with unique exception of Geoff Harcus as full member.

The League sought to bridge the barriers between Aboriginal and European communities, and the Coolbaroo dances contributed to this aim. Europeans were invited to the dances but they were not to have any control in running the organization. The League also endeavoured to manage any tensions between Aboriginal groups.

What Noongar, and all Aboriginal people wanted was control over our own affairs, not ‘rights’ based on European values. Under government law at the time, Noongars did not have citizenship rights. If we were eligible for citizenship we had to cut all ties with our families and friends who didn’t have citizenship. The League advocated for equal rights for Aboriginal people but not at the expense of loss of our identity and community. Not least of all, and contrary to the government view, we Noongar already saw ourselves as citizens in our own country.[ii]

The Dances

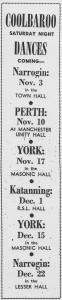

The Coolbaroo dances held in the Pensioner Hall outside the restricted area in East Perth were a highlight of the week for many Noongar people in the 1940s and 50s. Attendances often reached 300. There was an emphasis on a family atmosphere and alcohol was strictly forbidden. Young Noongar performers like Gladys Bropho sang with the band and Ronnie Kickett played the drums. There were also poetry recitals, stories, impersonations, and the ‘Miss Coolbaroo’ competition. The club attracted musicians and artists from interstate and internationally, incuding the attention of Nat King Cole and visits from Albert Namatjira and the Harlaam Globetrotters. The club closed for a time in 1948 and re-opened in the early 50s, with Bill Bodney, Ronnie Kickett and a ‘new generation of Noongar’.[iii]

Roma Loo talks about the Coolbaroo Club dances (oral history)

What Life was Like for Noongar

From 1927 until 1954, Noongar people were subject to oppressive laws, including the prohibited area, which consisted of five square kilometres in the centre of Perth. The prohibited area was introduced by A.O. Neville under the 1905 Act to discourage Noongar from loitering and gathering in large numbers. Noongar who worked in the city and within the prohibited area were required to carry identification and a pass. As there was also a night curfew, we had to have permits to travel after 6pm.[iv]

After World War II returned Aboriginal soldiers were not given any of the privileges afforded to European soldiers, such as land grants and pensions, or even enjoying a drink with our mates at the pub.

There were laws preventing sexual relations between blacks and whites, racially segregated schools and ‘blacks only’ train carriages. Often milk bars refused to serve Noongar and we were expected to sit at the front at the cinema and at the back of buses.

Westralian Aborigine

The League published its first bi-monthly newspaper, the Westralian Aborigine in 1953. It offered an alternative to the mainstream press and was significant in that it had Aboriginal editorial control and gave a voice to Noongar. The paper had some 600 subscribers.

The Coolbaroo dances were advertised there, as well as jobs. Sometimes, you could just be looking for a person you’d not seen in a while.

Achievements

The Coolbaroo League brought Noongar communities together, empowering us. It gave us a much needed political voice and autonomy. Historian, Anna Haebich wrote: ‘The Coolbaroo League was a conscious attempt to address the lack of political and civil rights and to improve the state of health, education and welfare for Aboriginal people’. Its most significant achievement ‘was that it resisted sustained pressures to transform itself politically or structurally into an organisation befitting an assimilation model’.[v]

The Coolbaroo Club continued until 1960 when Ronnie Kickett died suddenly (aged 29) and ‘the life went out of it’.[vi] From the Coolbaroo League, the Aboriginal Advancement Council was formed, and later, the Aboriginal Rights Council. They continued to fight for Aboriginal rights and recognition. In 1967 there was a national referendum where a majority of people voted to amend the Commonwealth Constitution. This provided the momentum for change that would progress Aboriginal rights.

Contemporary

In 1995, Stephen Kinnane’s film Coolbaroo Club was released. More recently, there’s been a resurgence of the Coolbaroo League. In 2009, the NAIDOC ball celebrated with a tribute to the Coolbaroo Club. The City of Perth held an exhibition in October 2010, with photographs, articles and interviews (see catalogue below). And the 2011 Perth International Arts Festival included Yirra Yaakin Theatre Company’s production of Waltzing the Wilarra written by David Milroy. On June 4, 2011, there was a Coolbaroo reunion dance held in Perth city.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Roma Loo; Mandy Corunna; Helena Murphy, nee Clarke; Corrie Bodney; Stephen Kinnane; Penny Robins; Ronin Films; City of Perth History Centre; Yirra Yaakin Theatre Company.

References

[i] Haebich,.A. Spinning the Dream:Assimilation in Australia 1950-1970, North Fremantle: Fremantle Press, 2008, p.285

[ii] Haebich, Spinning the Dream, p.285.

[iii] Kinnane. S. Shadow Lines, Fremantle: Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 2003, p.350.

[iv] Haebich, Spinning the Dream, p.280.

[v] Haebich, Spinning the Dream, p.286.

[vi] The Coolbaroo Club. Director Roger Scholes, Ronin Films,1996.