Art

Noongar Art

The traditional home of the Noongar people lies in the South West of Western Australia. Since the Nyittiny or the beginning of time Noongar people have shaped and formed the culture of our boodja – land, and in our contemporary society, employ the arts as a way of continuing to influence how we see our environment, our history and ourselves.

“Noongar art is so different to every other style of Indigenous art due to historical factors that began with colonisation,” Noongar community cultural development officer at the Bunbury Regional Art Gallery, Sandra Hill said.

“The contemporary style that Noongar artist’s use today is a direct result of white intervention back in the ‘mission’ days when Noongar people were removed from our land and from our traditional culture.”

Noongar art practice is distinctive. It is strongly influenced by the traditions of Carrolup, a painting style that emerged from the Carrolup Mission in the 1940s. The Carrolup artists were children who adapt the western style of capturing the landscape to their own cultural sensibilities. Today, Noongar artists are diverse in their practice, using a wide range of images and techniques in their work, but the references to those child artists of decades past are often still apparent.

Carrolup Artwork

More than 100 works of art produced by Noongar children who were confined at the Carrolup Native School and Settlement during the 1940s and 1950s have been returned to WA from America. The paintings, which are now well known, were so distinctive and technically sophisticated that they received widespread international acclaim when they toured around Europe in the 1950s. US businessman, Herbert A Myer, acquired the paintings and donated them to the Picker Art Gallery, which is located at the Colgate University in New York, in 1966 where they were ‘lost ‘and languished until 2004 when a visiting Australian-based art scholar, Professor Howard Morphy, immediately recognised them as the work of the Noongar children at Carrolup. The 119 pieces of art are mostly pastel landscapes often rendered in vivid shades of orange, yellow and blue depicting images of Noongar people and wildlife scenes reflecting designs rich in Noongar culture.

Some of the paintings incorporate Noongar and European elements, and because of their distinctive use of colour and light (especially in the sunsets), are regarding as having had significant influence on modern Aboriginal artists. A number of prominent Aboriginal artists spent time at Carrolup. Along with Roelands, Gnowangerup, and Moore River (also known as Mogumber, which featured in the film The Rabbit-Proof Fence), Carrolup was one of the main institutions where Aboriginal children (and especially those of part-European ancestry) were taken and confined after being forcibly removed from their parents under government policy designed to prevent them from being raised as Aboriginal. This policy is now infamously known as the Stolen Generations.

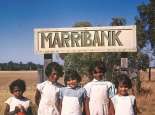

Carrolup, which is located near Katanning, operated as a Native Settlement between 1940 and 1951, when the land and all assets were handed over to the Baptist Union to become the Marribank Farm School, although it was not known by that name till later. The paintings were subsequently acquired by Florence Rutter. The paintings were produced during the 1940s by the children aged between five and fourteen years, who were encouraged by their teacher and school principal, Noel White, to wander through the local bush to make sketches of what they saw. The sketches were later turned into distinctive paintings in the classroom without the benefit of any formal instruction.

The paintings caused an international sensation when they were exhibited in the early 1950s in a tour organised by Florence Rutter at the end of the European exhibition tour and were then effectively ‘lost’ until they were discovered at the Picker Gallery at the Colgate University in 2004.

Repatriation of the paintings became an issue in 2006 after Colgate lent the works so they could be exhibited as part of the Perth International Arts Festival. Eventually, Herbert A Myer’s children approved the repatriation of the paintings to Curtin University in Perth because Curtin had the highest number of Noongar student enrolments of any Australian university and because Curtin was seen as an institution that would preserve the works in perpetuity.

Jeannette Hackett, vice chancellor at Curtin has said that Curtin will exhibit the works locally and nationally, with special emphasis on locally, to ensure all Noongar people have access. She said the artworks will be used for research, and that there is also the potential for a scholarship program between Curtin and Colgate universities focused on Noongar students.

“Their influence (Noongar artists Revel Cooper and Bella Kelly from Carrolup) made me want to paint, but it wasn’t until 1990 when I joined the TAFE art course in Katanning that I got really serious about doing art,” Athol Farmer said.

The Noongar Ascendancy

When the Art Gallery of WA held its first comprehensive survey of Noongar art in 2003 it was shaped by the intense curiosity of Brenda Croft, then AGWA’s indigenous curator. Where, she wondered, were the Rover Thomases and Mary McLeans of wheatbelt and forest country?

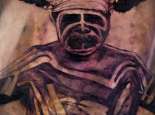

Noongar Artists

The list of Noongar artists provided are just a few, read their biographies and enjoy their artwork.

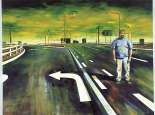

“I try to paint places that I know and wish to be at,” Graham said. “My wife is my inspiration”.

“My art is a reflection of me,” said Ian. It is my way of expressing my spiritual beliefs as well as the beliefs of my ancestors. My art reflects the way I see my country and people,” he said.

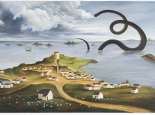

“Many people assume my work is purely traditional; a common stereotype applied to many Noongar artists from the south of Western Australia,” Charlie said. “I am breaking that stereotype, as much of the work I do is contemporary although I do retain some traditional elements.”

Lance Chadd (TJYLLYUNGOO). Art by Lance Chadd