Language

Kaya (Hello). Drawn by Roni Forrest for the Aboriginal Cultural Expo at Curtin University, 22 March 2013. Courtesy of SWALSC

Nyoongar language from the south west region of Western Australia

Noongar Words

kaya – hello

wanju – welcome

nidja/yimniny – here

djurapin – happy

nyininy/nyin –sit

Nih/ni – listen

kaartdijin – knowledge, learn

“From the past, today, tomorrow and the future”

Kaya noonakoort. Wandju, wandju, nidja Noongar Boodja. Nguny djurapin, nguny koort djurapin wanganiny noonakoort. Nyininy, nih wer kaartdjinin Noongar wangkiny. Noonakoort kaartdijin wangkiny deman, maam, ngarnk wer boordier kura kura.

Hello everyone. Welcome to Noongar country. We are happy, our heart is happy to be speaking with you all. Sit, listen and learn about Noongar language. We Noongar people were given our knowledge through the oral tradition from our grandfathers, grandmothers, fathers, mothers and Noongar bosses long long ago.

An early colonial also observed and recorded our Noongar tradition: “I have reason to believe that their [Nyungar] history and geography are handed down from generation to generation orally.” Robert Menli Lyon, 1833.

Noongar is the official language of the Aboriginal people of the south-west of Western Australia.

Nyungar language has a harmonious quality, and it is a real treat to hear two fluent speakers in conversation.

Noongar Elder Ralph Winmar in van den Berg, Collard, Harben and Byrne, Nyungar Tourism in the South West of Western Australia, Murdoch University, 2005

The word Noongar means ‘a person of the south-west of Western Australia’, or the name for the original inhabitants of the south-west of Western Australia’. While Noongar is identified as a single language, there are several ways of pronouncing it, which is reflected in the spelling: Noongar, Nyungar, Nyoongar, Nyoongah, Nyungah, Nyugah, Yungar and Noonga.

Our language is made up of fourteen different dialects. Noongar dialects have changed over time, incorporating and mixing with English. Many Noongar people of today grew up speaking English in school and Noongar at home. The kurrlongurr – children who were taken away to missions – the Stolen Generations – were forbidden from speaking our Noongar language.

In 1932 I was going to school at the [Gnowangerup] mission. And while I was in the school, see I talked a hell of a lot of Aboriginal talk. Matter of fact I didn’t learn to speak English properly until I was about seven. And I’m talking with my cousin now … So one of these girls … she told a teacher, reckoned that I was swearing at her, I was swearing. But I wasn’t swearing. It wasn’t swear words I was using. So teacher come along to me and she said, “You stop that talk”. And I looked at her, you know, she said, “You, you! We don’t want any heathens in this school”. She said, “If you talk like that you can get out”. She didn’t have to tell me twice to get out. I was out alright. I just wheeled around, I didn’t have – only had a slate and a pencil to leave behind, but I took off and I went.

Hazel Brown, oral history, SWALSC, 2008

Joe Northover – Minningup pool

Joe Northover talks about Minningup Pool on the Collie River

Audio Transcript

We come here to this place here, Minningup, the Collie River, to share the story of this area or what makes it so special. It is the resting place of the Ngangungudditj walgu, the hairy faced snake. Baalap ngany noyt is our spirit and this is where he rests. You have big bearded full moon at night time you can see him, his spirit there, his beard resting in the water. And we come to this place here today to show respect to him plus also to meet our people because when they pass away this is where we come to talk to them. Not to the cemetery where they are buried but here because their spirits are in this water. This is where all our spirits will end up here. Karla koorliny we call it. Coming home. Ngany kurt, ngany karla – our heart, our home. This, our Beeliargu, is the river people. So that’s why we always come to this Minningup. It’s very important.

This is the important part of the river, of the whole Collie River and the Preston River and the Brunswick River, because he created all them rivers and all the waters but here is the most important because this is where he rest. So whenever we come back now – my cousin died the other day so we come back here, bring his spirit home because this is where he belong here. They will bury him with his mother and you sing out to him. Ngany moort koorliny. Ngany waanginy, dadjinin waanginy kaartdijin djurip. And we come and look there and talk to you old fellow. Your people have come back. Ngany waangkaniny. I talk now. Balap kaartdijin. Listen, listen. Palanni waangkaniny. Ngany moort koorliny noonook. Ngany moort wanjanin. Your people come to rest with you now. Listen old fellow, listen for ’em, bring them home. Karla koorliny. Bring them home and then you sing to them. (Singing in language) And then chuck sand to land in the water so he can smell you. That’s our rules. Beeliargu moort. That’s the river people. That’s why this place important.

Hey, I’m super keen to learn to speak more fluent language, and my girl always asking me what the noongar word for this n that are. Just wondering if you know of any language courses running for us wadgellas, round Perth. Cheers.

Kym Rowe

For nearly two centuries Noongar language has adapted to the impacts of colonisation and survived government reserves and missions, where it was also forbidden for Noongar people to speak our language. Noongar language has also been adapted into the local English vocabulary, notably with places, plants and animals. Consisting of 14 different dialects, Noongar is an oral language and the spelling of it is variable.

Noongar Prayer

Ngaala Maaman Waangk

Ngaala Maaman ngiyan yira moonbooli Moodlooga.

Kooranyi noonak korl. Noonak waangk, yoowarl koorl,

birdiyar ngaala boodja noonook woorn noonak kooranyi kaalak.

Nyinyak ngaalang nidja kedela ngaala mereny.

Nyinya nyinyak ngaalang ngaala wara waarniny.

Ngaalak nyinya nyinyak, baalang ngiyan waarn wara ngaalang.

Yoowart koorl ngaalang moort-moort djooroot. Maaman maar barang ngaalang, Noonak waangk birdiyar. Noonak moorditj, noonook ngaangk yira.

Kalyokool, kalyokool.

Kaya

FATSILC, The Federation of Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Languages & Culture (Corporation)

Here are some Noongar words for you to practice.

marlee – swan, beeliar – river, boorn – wood/tree, nyingarn – echidna, koorlbardi – magpie, kitje – spear; koornt – camp, balga grass – balga tree

Noongar people also have many names for places and towns throughout our boodja. Some well known places in Whadjuk boodja are: Wadjemup, now known as Rottnest Island; Ngooloormayup, now known as Carnac Island; Meeandip, now known as Garden Island; Gargangara north of Armadale; Goolamrup, now known as Kelmscott; Dyarlgarro Beelya, now named the Canning River; and Derbal Yiragan, the Perth estuary waters. Some Noongar place names and their meanings are in Noongar Wangkinyiny.

A lot of the Nyungar history and culture have come from word of mouth from our Nyungar elders.

Craig McVee in van den Berg, Collard, Harben and Byrne, Nyungar Tourism in the South West of Western Australia, Murdoch University, 2005

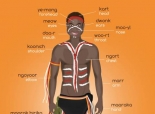

The late Tom Bennell (Yelakitj), shared this story about moort (family) relationship names and how moort would have wangkiny (talked) with each other:

Deman is the name for Grandmother and Dembart is the name for Grandfather. I say dembart yaarl koorl – Grandfather come here or deman yaarl koorl – Grandmother come here. She is saying this to the daughter of her daughter. Wort koorl deman, that means go away grandmother.

They might go to some of their other relations, they don’t call them uncles they call them konk and their brother-in-law they call them ngoorldja. They call their brother ngoony and sister djook. A child is called a nop. A maam (man) calls his yok – koorta. Koort is heart. Cousins well they call them same – grandfather, same as their cousin, dembart.

Noongar Elder Tom Bennell in Collard, Harben and van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy’ website, 2004

Dialects

In the late 1930’s, anthropologist Norman Tindale identified 14 language groups within Noongar country: Amangu, Yuat, Whadjuk, Binjareb, Wardandi, Balardong, Nyakinyaki, Wilman, Ganeang, Bibulman, Mineng, Goreng, Wudjari and Njunga [i] See Noongar Explained more information. More current is Horton’s map of Aboriginal Language Boundaries.[ii] It differs slightly from Tindale’s in that Horton removed the boundary between Wudjari and Njunja on the south coast near Esperance and named the group Wudjari. Click on the link to view Horton Map.

The main difference between the Noongar language groups is pronunciation, but because the groups are geographically and ecologically distinctive, there are also regional vocabularies. Some words may only be known in one region of Noongar country, particularly plants, which are unique to the local climate and soil type. Overall there are many common words in Noongar, for example: kaya = hello, moort = family, boodja = country and yongka = kangaroo. These words are used everyday but they sound slightly different from region to region.

But of course with the Nyungar culture we are basically all the same but there are some differences with regards to our language. And of course you know you have to have your language because the language that I refer to might not necessarily be the language that other Nyungar people refer to. But it is Nyungar language and not many people realise that this is the case.

Where we get the confusion sometimes with our Nyungar language is the writing down of it. Because you get one linguist or an Aboriginal person and another person writing it down and another person reading it, doesn’t necessarily come out the way it was written down, and then it creates a bit of confusion but we all generally know what we are talking about.

Doc Renolds in van den Berg, Collard, Harben and Byrne, Nyungar Tourism in the South West of Western Australia, Murdoch University, 2005

This variation in our Noongar language reflects both regional dialect differences as well as an attempt by the fourteen language groups to retain, in a modern Australian society, a sense of independence and difference within.

Identity

Speaking Noongar immediately lets everyone know where we come from. It reinforces our group identity, which binds land and people. Noongar language is not only a way of communicating; it is a statement of who we are.

Nyungar wangkiny or speaking and understanding our language is central to our identity. We need to commit to reinvigorating our cultural heritage and teach our kurlonggur (children) so that they know where they come from, once they learn the language they can start to make that connection to their cultural identity and heritage and go forward with pride into the future.

Sandra Harben, SWALSC, 2012

My name is Bianca. I am a Noongar. I know who Hagan is. (Yagan’s biography). The wedjella cut his body up into pieces and put it around Australia. Hagan was a Noongar. I know Noongar words. Mooly is your nose, dwonk is your ear, marr is your hand and ngorrolick is your teeth … I love going to Badgaling, we get gum from the trees, look for yonga (kangaroo)… when I am in the bush I feel free.

Bianca, 9 years old, interviewed February 2013, SWALSC

Language and Trade

The common language between neighbouring Noongar dialectal groups enable us to communicate and trade. Noongar have always been engaged in trade right back well before settlement. Trade took place before the settlers actually came to this country. Trade between our people and people from other nations is well documented. Our people went as far as Uluru and the centre of Australia and those people from there came back as well.

Travelling was a big part of ceremony and a big part of trade in those days as well. People going to ceremony would be going on business but when it wasn’t ceremony time those people would still go and visit other areas and then when they would come for a visit they would bring with them gifts and exchange.

The different groups would bring stones and ochres and all sorts of different things from their country that didn’t exist in Nyungar country and that is a form of “paying their way” which puts them into the category of trade and tourism. So trade in Nyungar country is very very old, thousands of years old.

Dr Richard Walley in van den Berg, Collard, Harben and Byrne, Nyungar Tourism in the South West of Western Australia, Murdoch University, 2005

“I used to listen to those stories and I remember [grandmother Yurleen Garlett] telling one of her nephews a story … that happened there. The story happened a long time ago and it is as follows”:

There was all the Nyungar or people who used to camp the Derbal or estuary [around Perth waters]. There were some fellas from the north; they came for some ceremony. They came and sat down and sang. They had come to trade and they brought some medicine and some fire. That was, like, along the river.

They reckoned that in the wintertime, it was cold, see, and these fellas who used to hunt up in the bush, they brought some things down, clothing and stuff (yongka booka [kangaroo skin cloaks]). These fellas only used to stay for a little while, while the ceremony was there and they used to exchange things, you know?

Noongar Elder Sealin Garlett in Collard, Harben and van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy’ website, 2004

Noongar Trade

Much of the trade that took place between the different Noongar groups was very dependent on the six Noongar seasons. One of the most well known Noongar trade fairs or meeting place was in Pinjarup Noongar budjar. It was known as the Mandura (Mandurah derives its name from this activity) which was a type of fair or meeting place where goods or presents were exchanged amongst the Noongar in the south-west during the Bunuru or summer season. Noongar from different areas brought their goods here for exchange.[iii] Daisy Bates records that Goonininup or Crawley Bay was a key camping place on a major trade route used by Nyungar travelling from other areas to Perth in order to trade for the highly demanded wilgi (red ochre).[iv]

Pinjarup Noongar would trade the following items at the Mandura:

• Burdun: a light gidgee, highly prized for the elasticity of the timber.

• Durda-dyer: a skin of a dingo tail, worn on the upper part of the forehead as an ornament.

• Ngow-er: a small tuft of feathers tied to a stick and worn in the hair for ornamentation.

• Niggara: a human hair girdle worn around the waist. • Nulbarn: a rope-like girdle made from possum hair, wound around the waist and used to carry the kylie (boomerang), tabba (knife), kodja (axe or axe heads) and the dowak (throwing stick). This rope was also used to tie up wounds.

• Tabba: a knife made of sharp pieces of quartz connected to a short wooden stick, as thick as a thumb, by kodja or blackboy tree gum.

• Wilgi: ochre used dry or mixed with grease for protection from the elements such as the sun and flies or mosquitoes. Also used during ceremonies.

Pibelmun Noongar would trade local goods such as:

• Booka/Boka/Bwoka: yongka (kangaroo) skin garment made from several skins of the female kangaroo and used for warmth and protection from the rain in winter.

• Burdun: a light, straight spear made from the mungurn (swamp wattle) collected from the local swamps.

• Choota: A possum or kangaroo skin bag used by the women to carry children or food collected while travelling between campsites.

• Gidgee-borryl: the dreaded quartz edged spear which in post-settlement times was glass tipped. It was up to ten feet long and about one inch in diameter and made from the mungurn (swamp wattle). This spear was made in the Ellensbrook and Wonnerup areas.

• Miro: the name of the south-west spear thrower used by Noongars to propel the aim of the gidjee.

• Weja: emu feathers used as ornamentation at ceremonies.

• Wonna: the women`s digging stick was about six feet long and and as thick as a broom handle. It was made from peppermint shafts. The wonna was fired for hardness and was used for digging, killing animals and fighting with other women. The wonna was always traded by women at the Mandura.

Yuat Noongar would bring for trade the following items, among others:

• Borryl: quartz used for the sharp edges on the gidgee and tabba.

• Dowak: a short heavy stick used for hunting animals and birds.

• D-yuna: a fighting stick used during wars and in friendly contests.

• Gidgee: a spear about two and a half metres in length.

• Kylie: a flat, curved piece of wood (boomerang) used for hunting animals and birds.

• Miro: a throwing board used by Noongar people to propel the gidgee. • Wirba: a heavy club traded from the northern areas.

Whadjuck Noongar would bring these items for trade:

• Boka: a kangaroo skin garment used for keeping warm and dry.

• Bo-ye: a rock for kodja, tabba or grinding stones.

• Bu-ruro: a possum hair neck band worn as an ornament.

• Bu-yi: a nut from the zamia plant that once treated, was fit to roast and eat.

• Dardark: a lime white clay used to paint the body at festivals.

• Kodja: a hammer or axe, broad and blunt at one end and sharpened at the other. Made by connecting a short strong wooden handle as round as a thumb, by kadjo or blackboy tree gum to the top of the handle.

• Wilgi – the highly demanded red ochre.[v]

So trade in Nyungar country is very, very old, thousands of years old.

Dr Richard Walley in van den Berg, Collard, Harben and Byrne,

Nyungar Tourism in the South West of Western Australia, Murdoch University, 2005

Place Names

Many places in the south-west have been named by Europeans, after European towns and people, such as Perth and Albany. Yet, there are nearly as many places that have been given Noongar names. The reason for this can be found in an early document from Governor Hutt. In a dispatch of British Parliamentary papers from Western Australia in 1840, Hutt wrote “…it is only an act of fair justice to the first inhabitants or discoverers of any spot, to retain the name that they may have conferred upon it.”[vi]

Some Noongar place names in Perth are: Balga, Beeliar, Willagee and Mirrabooka. See history of suburb names courtesy of Landgate, WA. The names of many south-west towns are Noongar in origin: Gidgegannup (place to make spears), Ongerup (place of the male kangaroo) and Goomalling (place to find possum).

Knowing the Noongar language can open up a new world into our culture and also give a sense of place. In Noongar language, Fremantle, Rottnest, Perth and Albany are known as Walyalup, Wadjemup, Gabbi Darbal and Kinjarling. Noongar names provide significant information about that place: Wadjemup is the place ‘where the spirits go’; Gabbi Darbal means estuary, ‘the place where salt and freshwaters mix’ and Kinjarling is ‘place where it rains a lot’.[vii]

Watch Noongar of the Beeliar for a sense of place around the Swan River.

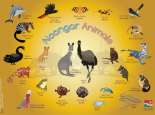

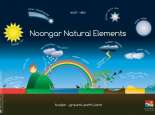

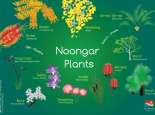

Plant and Animal Names

Adopted into the local English language are also many Noongar plant and animal names: Marri, Karri, Jarrah, Quenda (Bandicoot), Quokka and Jilgie. Early explorers had no English names for many of the species that occur in the south-west of WA. Much of the biodiversity in Noongar country is not found anywhere else in the world.[viii] In this way, names, knowledge and the habitat of south-west plants and animals share an identity with, and are locally understood by Noongar people.

Noongar Language Studies

Early attempts to develop Noongar word lists were done by explorers and colonists like Flinders, King, and Nind at Albany. In 1833, Robert Lyon published articles on Noongar customs manners and dialects.[ix] George Fletcher Moore published A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia in 1842 and included the descriptive vocabulary in his Diary of Ten years of an Early Settler in Western Australia (1884).[x]

In 1840, George Grey published A Vocabulary of the Dialects of South West Australia in London.[xi] Notes from Grey’s Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery in North West and Western Australia, Vol. 2, (of 2) published in 1841, identify a common language between Perth and King George’s Sound (Albany).[xii] The memoirs of Bishop Rosendo Salvado from New Norcia were published in 1851. They contain a word list of local Noongar people from the Victoria Plains.[xiii] The efforts of others who were conversant, and in some cases, fluent in local Noongar language, such as Brady, Hutt, Armstrong, Symmons and Bussell of Vasse, are acknowledged in many of the published works.

In 1992 the first Noongar Dictionary produced by Noongar people was compiled and published by Rose Whitehurst for the Noongar Language and Cultural Centre. It uses the spelling for Noongar words agreed at that time by elders from across Noongar country. This spelling is still used when teaching Noongar language in schools. The Dictionary also explains the sounds, spelling and pronunciation of Noongar words.[xiv]

In the same year, the Western Australian Museum published a Nyoongar Word List by Peter Bindon and Ross Chadwick. This contains an assemblage of the word lists gathered by Europeans in the early years of the colony, and described above, as well as work from Curr, Bates and Hassell.[xv] The spelling is as it was written by the original non-Noongar authors rather than the current accepted spelling.

Noongar Grammar

In Noongar language, words are ordered differently than in English. The subject comes before the verb in English and the object follows, but in Noongar, the word order is subject – object – verb. To explain that men are hunting kangaroo, in Noongar we say: ‘maam yonga ngardanginy’. Translated into English this would be maam = men, yonga = kangaroo and ngardanginy = hunting.

Impact of English and Settlement on Noongar Language

Through the 1800’s and up to the mid-20th century, Noongar children weren’t allowed to speak their language in schools and missions. While missions set out to break the chain of learning Noongar culture and language, grouping Noongar people together allowed parents and Elders to continue to pass language on to the younger generation. In this way, Noongar language has been kept alive.

In the 20th century, if a Noongar person wanted to become a citizen, he or she had to renounce their Noongar identity and were not permitted to speak their language or communicate with family or friends. This was orchestrated by the government of the day to abolish Noongar language and identity. Many people however, rejected citizenship because they were not prepared to give up their Noongar culture.

Doolan Leisha Eatts talks about Badjaling reserve and how the missionaries stopped the children from speaking Noongar.

And that was only one thing, the other thing was to teach ’em not to talk in their language, to teach ’em to talk in the English

Doolann Leisha Eatts, oral history, SWALSC, 2003

Language Living On

Noongar language has survived despite the impact of settlement and dominance of English. The custom of teaching Noongar continues to be handed down from Elders to children. In the past, as Kevin Fitzgerald said, ‘a fly lizard was put on a child’s tongue for them to learn how to pronounce Noongar language’.[xvi]

See long time ago, this is traditional law go back long time with Noongar for a little kid to talk Noongar, old fella get ‘im in ‘is arm and get the fly lizard and he say something and put it on his tongue, and put it away, and that kid he’ll grow up talking Noongar, fluently.

Kevin Fitzgerald, oral history, SWALSC, 2006

Rosezanna Jetta learning Noongar language from Charmaine Bennell at Djidi Djidi school in Bunbury.

Courtesy The West Australian

Today, there are many Noongar language classes in schools and TAFE. Noongar people are often invited to speak in language at opening ceremonies and at places which have long been sacred to us. There are several projects which have begun to record the oral history and language of older Noongar men and women. Efforts have been made in our Noongar community to re-invigorate language. Classes for Noongar and non-Noongar alike aid in the transmission of knowledge. For example, Langford Aboriginal Association in Perth offers regular classes in Noongar language for adults and children. Revival of our language is also evident with Noongar being taught in addition to English in primary schools like Carralee in Willagee, Morditj Noongar in Middle Swan, Ashfield Primary School and Djidi Djidi School at Bunbury. The Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education and Batchelor Press have been working towards revitalising Noongar language. In the Yallingup region, the Wardan Centre brings an increased understanding of our language and culture through education programs. The South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council are producing posters in Noongar language.

Watch Kylie Farmer [Kaarljilba Kaardn], Noongar actor, TV presenter, writer and director, in her inspiring talk to TEDxManly in February 2014 on the topic Keep Our Languages Alive

All Should Speak Nyoongar. Courtesy The West Australian, 9 July 2002

If you wish to purchase Posters from SWALSC please fill in the SWALSC ORDER FORM.

References

[i] Tindale, N.B. Aborigines of Australia. ANU Press, Canberra, 1974

[ii] This map is just one representation of many other map sources that are available for Aboriginal Australia. Using published resources available between 1988-1994 this map attempts to represent all the language or tribal or nation groups of the Indigenous people of Australia. It indicates only the general location of larger groupings of people which may include smaller groups such as clans, dialects or individual languages in a group. Boundaries are not intended to be exact.

[iii] George Fletcher Moore, A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia (London: Orr, 1842), http://books.google.com.au/books?id=1e8UAAAAYAAJ&dq=George%20Fletcher%20Moore&pg=PR1#v=onepage&q&f=false,p.68

[iv] Bates, D. Aboriginal Perth: Bibbulmun Biographies and Legends. P.J. Bridge (ed.), Hesperian Press, Carlisle, 1992, cited in Vinnicombe, Patricia. Goonininup: A Site Complex on the Southern Side of Mount Eliza: An Historical Perspective of Land Use and Associations in the Old Swan Brewery Area. Perth: West Australian Museum, 1989, p.18

[v] George Fletcher Moore, A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia (London: Orr, 1842), http://books.google.com.au/books?id=1e8UAAAAYAAJ&dq=George%20Fletcher%20Moore&pg=PR1#v=onepage&q&f=false,p.68

[vi] Despatch from Hutt to Marquis of Normanby, 11 February 1840 with enclosure, British Parliamentary Papers, Papers relating to Aborigines, Australian Colonies, 1844, Colonies, Australia, Volume 8, Shannon University Press, 1968, pp.372-3

[vii] Bates, D. Aboriginal Perth: Bibbulmun Biographies and Legends. P.J. Bridge (ed.), Hesperian Press, Carlisle, 1992

[viii] Beard, J.S., Chapman, A.R. and Gioia, P. Species Richness and Endemism in the Western Australian Flora. 2000. Journal of Biogeography 27: 1257-1268.

[ix] Lyon, Robert Menli. ‘A Glance at the Manners, and Language of the Aboriginal Inhabitants of Western Australia; With a Short Vocabulary’, Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal. vol 1, no 13, 30th March, 1833, pp.51-52

[x] Moore, G.F. Diary of ten years eventful life of an early settler in Western Australia; and also, A descriptive vocabulary of the language of the Aborigines, London: M Wallbrook, 1884

[xi] Grey, G. A Vocabulary of the Dialects of South West Australia. L. and W. Boone, London, 1840

[xii] Grey, G. Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery in North-West and Western Australia, During the years 1837, 38 and 39, under the authority of Her Majesty’s Government. Describing many newly discovered, important, and fertile districts, with observations on the moral and physical condition of the Aboriginal Inhabitants &c. &c., T. and W. Boone, London, 1841

[xiii] Salvado, Dom Rosendo Memorie Storiche dell’Australia. 1851 (edited and translated in 1977 by E.J. Storman).

[xiv] Whitehurst, Rose (compiler). Noongar Dictionary: Noongar to English and English to Noongar. Noongar Language and Culture Centre (Aboriginal Corporation), Bunbury, 1992

[xv] Bindon, Peter and Chadwick, Ross. A Nyoongar Wordlist from the South West of Western Australia. Western Australian Museum, Perth, 1992

[xvi] Kevin Fitzgerald, oral history, South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council, 2006

Kaya (Hello). Drawn by Roni Forrest for the Aboriginal Cultural Expo at Curtin University, 22 March 2013. Courtesy of SWALSC