Wagyl Kaip and Southern Noongar

The town of Albany is firmly situated in the Wagyl Kaip and Southern Noongar region of Noongar booja – country. Noongar people have lived in this part of booja since the Nyittiny – creation times.

Since time immemorial, the people of the Wagyl Kaip region have shared and cared for country.

The landscape of the Wagyl Kaip includes the Stirling Ranges, Mt Madden, and deep bays, forests and extensive plains that hold a variety of natural resources. Rivers and waterways include the Kalgan, King, Stokes, Fitzgerald, Wellstead, Gordon, Pallinup and Cullum Inlet.

We used the coastline, as well as the rivers, swamps and vegetation beyond it. Our traditional foods consisted of birdlife, eggs, plants, small and large animals like kangaroo, emu and goanna, as well as estuarine fish. Traditionally, we lived in the coastal regions during the summer months and moved inland for shelter with the onset of winter. At Oyster Harbour, close to the mouth of the Kalgan River, Minang Noongar made fish traps from stone. The fish were trapped in the harbour as the tide went out.

Avril Dean shared her brother Jack Williams’ story:

Now I just want to tell this story as a tribute to my brother, Jack, who’s passed away, and he was our historian. And he told this story about the traditional people and how they used to go and catch salmon to feed the whole tribe. So long ago, and it happened right up until our parents were young people, it was still happening. And it’s actually happened very, very recently where the same thing has happened. But this time the dolphins brought the salmon in, because there was Noongars on the beach.

And they said they just went crazy ‘cause they were catching the salmon with their hands. So – long time ago, they used to come down to the coast when the salmon were running, when they were at their prime condition. And they had a special man and only one man was allowed to do this. This was tribal lore. They used to have this special man that had – he had to have a beard and the wind had to be blowing in a certain direction. And he’d have to light a fire on the beach. And he’d have to have a fire and make it a smoky fire so that the smoke could blow out. And he used to sit on the beach with his legs crossed and he used to tap his sticks together. And he’d sing, djock, djock, djock. And then all of a sudden he would see the dolphins start to work. And they’d go around a big school of salmon and they’d go round and round and round and work ‘em around like, like a sheep dog does, I suppose, if you say that. And then they used to bring them right in to the beach and they’d go into a real frenzy ‘cause they’d be bringing them right in, bring them right down to the beach and then the whole tribe, even children could come in and catch them.

In 1790, British explorer George Vancouver arrived on the southern coast of Western Australia. Despite naming King George Sound, various inlets and bays, and mapping the area, he did not encounter any Noongar. But he reported evidence that Noongar were there. He wrote that he found a ‘native village; fresh food remains near a well-constructed hut; a kangaroo that had apparently been killed with a blow to the head; a fish weir across what is now called the Kalgan River; and what appeared to be systematic firing of the land.’[i]

The first impressions of the Wagyl Kaip landscape and of Noongar people were recorded by Phillip Parker King when he visited in 1821 and spent time with local Noongar.

In 1826 Major Edmund Lockyer established an army garrison at King George Sound with the intention of building a penal settlement. When he came across the Noongar system of ‘payback’, he was less concerned with building a relationship with local Noongar than he was about imposing British law onto Noongar culture and lore.[ii]

Noongar often led explorers through the region, probably without any idea of the consequences. Our intimate knowledge of the land and its waterways and fresh water was invaluable to the British. Many original walking trails used by Minang Noongar eventually became roads.

Mokare, a Minang Noongar, was a young man in his twenties when he met the British explorers at King George Sound in the mid 1820s. During this early period he was the Noongar the new settlers wrote about most. Mokare was the intermediary, guide and close friend of several of the newcomers to the region, in particular, Captain Collet Barker. Mokare died in June 1831, most likely from influenza – introduced by the Europeans. He was buried close to what is now the Albany Town Hall. On the basis of what Mokare told the Europeans about Noongar culture and language, Isaac Scott Nind published a Noongar vocabulary, and an account of our people, culture and customs. Tools used by Noongar people, and recorded by Nind include:

- Kodja – axe for cutting and hammering, such as cutting footholds into trees and extracting bees-nests and possums.

- Taap – knife, which among other things, was used to cut seal flesh.[iii]

Most Noongar were wary of initiating contact with the British, but they were curious, judging the “foreigners on individual merit as they saw it”.[iv] In the beginning, there were tentative relationships and the exchange of gifts.[v] However, tensions grew and violence erupted as the settlement of Albany expanded and Europeans made their way further inland, encroaching on resources and taking up Noongar land.

Traditionally, Noongar maaman (men) hunted kangaroos for food and for clothing in colder months. When we hunted for kangaroos, we fired the land first. With the arrival of Europeans, Noongar also shot kangaroos for the export of their skins. This was one way the Noongar community maintained traditional links to the land, while adapting to the new European economy. However, Europeans also shot large numbers of kangaroos for their skins, often leaving the carcasses where they shot them. In 1848 Captain J. Lort Stokes expressed concern that this was adversely impacting on Noongar traditional ways of life’.[vi] By 1853 the shooting of kangaroos got to such large numbers that legislation was passed to prohibit certain activities unless shooters had a license. (See the Kangaroo Ordinance, 1853)

In 1852 Annesfield School was established in Albany by Ann Camfield and Anglican Archdeacon Wollaston. The institution aimed to remove Noongar children from their families and to ‘civilise and Christianise’ them.[vii] In 1867 Bessy Flower and four other Annesfield girls sailed to Melbourne; Bessy to teach at the Ramahyuck Mission in Gippsland, Victoria, and the others to marry mission trained men.

Noongar continued to care for country, hunting and gathering food in the traditional way.

Ravensthorpe massacre: In 1880, a group of Noongar was massacred a few kilometres from the town of Ravensthorpe in the area known to Noongar as Cocanarup. John Dunn, a farm worker, attacked and violated a young Noongar girl. He was subsequently killed – according to the Noongar lore of payback – by Yandawulla Dibbs and a group of local Noongar men. Dunn’s overseer sent out word of the killing, and returned with a large group of armed settlers. Up to 30 Noongar men, women and children in the area were killed.

Noongar to this day still find it hard to visit the place where our ancestors were killed and suffered such injustice.

To find out more, see Roni Forrest’s Kukenarup – Two Stories: A Report on Historical Accounts of a Massacre Site at Cocanarup Near Ravensthorpe WA.

Carrolup Native Settlement opened in 1913 and people from the Katanning area were moved there. It closed in 1922, but was reopened in 1938. In 1952 it became Marribank Baptist Mission and ran until 1970.

Children at Carrolup Native Settlement, such as Revel Cooper and Reynold Hart, produced the now internationally famous Carrolup School of Art.

Many of our people from the Wagyl Kaip region were affected by World War One. Noongar people were barred from enlisting, on the grounds of race, even though the need for more troops was dire. Later in the war, those Aboriginal Australians with one European parent were accepted into the armed forces. Many Noongars enlisted anyway by concealing their family background. See War Service for more information.

Albany has special significance for soldiers, as it was the last port of call for troops leaving for the war in Europe. For many, this was their last view of Australia.

Michael Connor was a Noongar man who worked as a horse breaker and labourer in Albany before joining the Australian infantry (48th Battalion) on 21 September 1915, at 21 years of age. He embarked from Fremantle in January 1916 aboard the transport ship SS Runic. Michael Connor died in France in June 1916 and was buried in the Lavallois-Perret cemetery. His name is recorded at the Australian War Memorial.

Noongar people were also involved in World War Two. When Noongar soldiers returned however, they were not recognised for their war efforts, nor were they granted the same privileges as white soldiers. Land settlements were granted to returned soldiers and also to Italian immigrants who had been prisoners of war and worked the land during this time. Although Noongar too had worked the land and served in the war, we were not granted land settlements.

Arthur Edward Morrison, a Noongar man, was born in 1919 and was a farmhand and rabbit trapper before joining the armed forces. He was a prisoner of war at Changi during the Second World War. Arthur Morrison died in 2000.

Augustine (Gus) Mindemarra was born in New Norcia on 15.6.1904. Prior to the Second World War he worked as a labourer. He enlisted in the Australian Army in December 1940. Mindemarra embarked for overseas service on the HMAT US 11A at Fremantle in July 1941. He died on 19.9.1973 in Katanning.

Falling stones were reported near four south-west towns in the 1940s and 50s. This included the Mayanup camps near the town of Boyup Brook. Many Noongars believe that the falling stones were associated with wayward spirits.

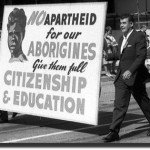

Referendum – The 1967 Referendum was a significant mark of recognition for Aboriginal people. Many Noongar have memories of how life changed for us afterwards.

Carol Pettersen explains what it meant to her:

And when this Referendum came along, it was really scary because after years of oppression, years and years of oppression and being punished for daring to be any different, all of a sudden they open a book to you and say, “Be black – it’s all yours.” And we were saying, “Oh no, hang on, this is a trick, you fellas, don’t take any part of that, you know.” “Don’t have nothing to do with that,” you know. It was very scary. So we didn’t – we didn’t take advantage of any of that stuff at all, those government programs, because if you were seen to be – see remember what the Commissioner said to my father? They had to be brought up as white children and they weren’t to be a burden on the State. Now for me to put my hand out for any government assistance is very scary, you know – I think, we got AbStudy but that’s about the only thing I ever got. Never ever took anything else.

Although Noongar people were counted in the next census after the Referendum, it did not confer citizenship rights. This created a demand for change and activism. Organisations such as the Aboriginal Advancement Council came out of this.

In 1998 the Wagyl Kaip Native Title claim was lodged. This was based on the 1996 Southern Noongar claim but with more ancestral families added.

In September 2006, the successful Single Noongar Claim handed down by High Court Judge Justice Wilcox, recognised that native title has not been extinguished across Noongar country.

In 2009 management of the Albany Fish Traps was handed over to a group representing the site’s traditional owners.

References

[i] Vancouver in R. Appleyard. ‘ Vancouver’s Discovery and Exploration of King George’s Sound’ in Early Days, Journal and Proceedings of the Western Australian Historical Society, 1986, pp.86-97

[ii] Host, J and C. Owen, It's Still in my Heart, This is my Country: The Single Noongar Claim, UWA Publishing, p.47

[iii] Host, J and C. Owen, It's Still in my Heart, This is my Country: The Single Noongar Claim, UWA Publishing, p.40

[iv] Host, J and C. Owen, It's Still in my Heart, This is my Country: The Single Noongar Claim, UWA Publishing, p.55

[v] Host, J and C. Owen, It's Still in my Heart, This is my Country: The Single Noongar Claim, UWA Publishing, pp.54-55

[vi] Captain J. Lort Stokes, letter to the Editor, The Inquirer, 8 August 1848

[vii] Donald S. Garden, Albany: A Panorama of the Sound from 1827, West Melbourne, Vic. Thomas Nelson, p.148