Northam

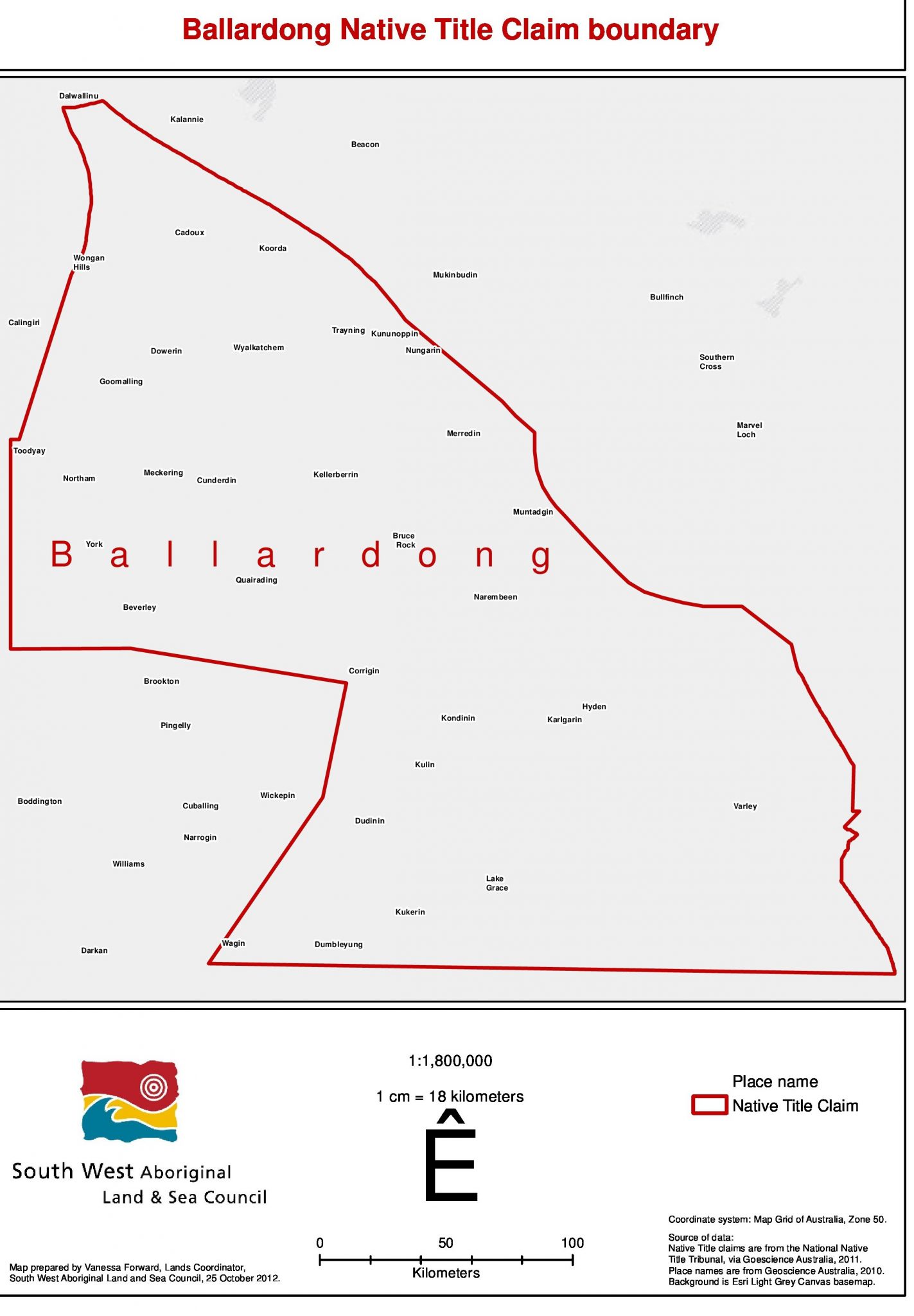

The town of Northam is firmly situated in Ballardong Noongar booja (country). Noongar people have lived in this part of booja since the Nyittiny – creation times.

Nearly 100 Noongar cultural sites exist in and around the towns of Northam, York, Toodyay, Mundaring, Kondinin, Hyden and the Avon Valley National Park. Throughout these areas there are mythological paintings, scar trees, animal traps, quarries, caves, stone arrangements and artefact scatters between 30,000 and 40,000 years old.[i]

In the York area there are two significant caves which are Noongar sites of art and rituals. Dale’s Cave contains hand stencilling and a circular motif painted in ochre, which is a pigment made from different soils. Frieze’s cave features ‘short, parallel orange-ochre painted strokes’.[ii] In the Hyden area another significant cave is Mulka’s Cave. It has a hand print on the ceiling of the cave.

Burlong Pool, just outside Northam on the Avon River, is an important place for ceremonies, hunting and camping for Noongar people.[iii] The pool is a spiritual and mythological site to which the river serpent, the Waugal, travelled underground from Bolgart. There the Waugal stayed in the long and deep pool during the summer months. [iv] Several Noongar sites exist near Burlong. These include mythological sites, paintings, and a reserve.[v]

Richard Ensign Dale, soldier and early explorer, travelled east of the Darling Mountains where he came to the Avon River. Although this was Noongar land, allotments were made available for Europeans for agricultural settlement by October 1830.

The Avon River also flooded that year. Noongars recounted that the flood of 1830 was so great and the land so marshy that kangaroos became bogged in it. [vi]

1832: Hostility between Noongars and Europeans increased as more explorers arrived in the Avon Valley area.[vii] As Europeans expanded their number of sheep and crops, Noongar people were deprived of their water holes and hunting grounds. The settlers demanded that soldiers were posted at York to protect them from the increasing conflict, and an outpost was established there.[viii]

1833: The town of Northam was gazetted.

1834: Agriculturalist, H.G. Smith travelled to Northam to view his grant of land with five volunteers and one Noongar man named Weenit. Noongar people, like Weenit, acted as guides for most European settlers.

Smith’s description of the Avon River is published in the Perth Gazette: The country he described was lush with native flora and fauna, with the Avon ‘abounding in kangaroos, musk and common wild ducks; also cockatoos.’ [ix]

As colonisation progressed there was continued resistance from Noongar people, as Europeans attempted to settle the outer eastern reaches from Perth, east of York. [x] There were numerous reports about the conflict in the area, including Gingin and Toodyay. Ongoing conflict led to measures being taken by the formative government, which put soldiers in charge of the district around Northam and York.

Violence continued between Noongars and Europeans. Noongars fought to take back what was once rightfully our land and resources. The Europeans resented their food and stock being taken. When settler, Sarah Cook and her infant were speared at Norrilong (between Beverley and York) to satisfy tribal lore, Governor Hutt created a Native Police Force to deal with the conflict.

Two brothers, Doodjeep and Barrabong were arrested and tried for ‘wilful murder’ in July 1840. They were later hung in chains at the scene of the crime. A year later, a Noongar man named Yambup was also convicted of the same crime and was sent to Wadjemup – Rottnest prison.[xi]

Under John Drummond, the Native Police forcefully suppressed Noongar resistance to European settlement.[xii]

After 1841, relations between Europeans and Noongars were generally peaceful.[xiii]

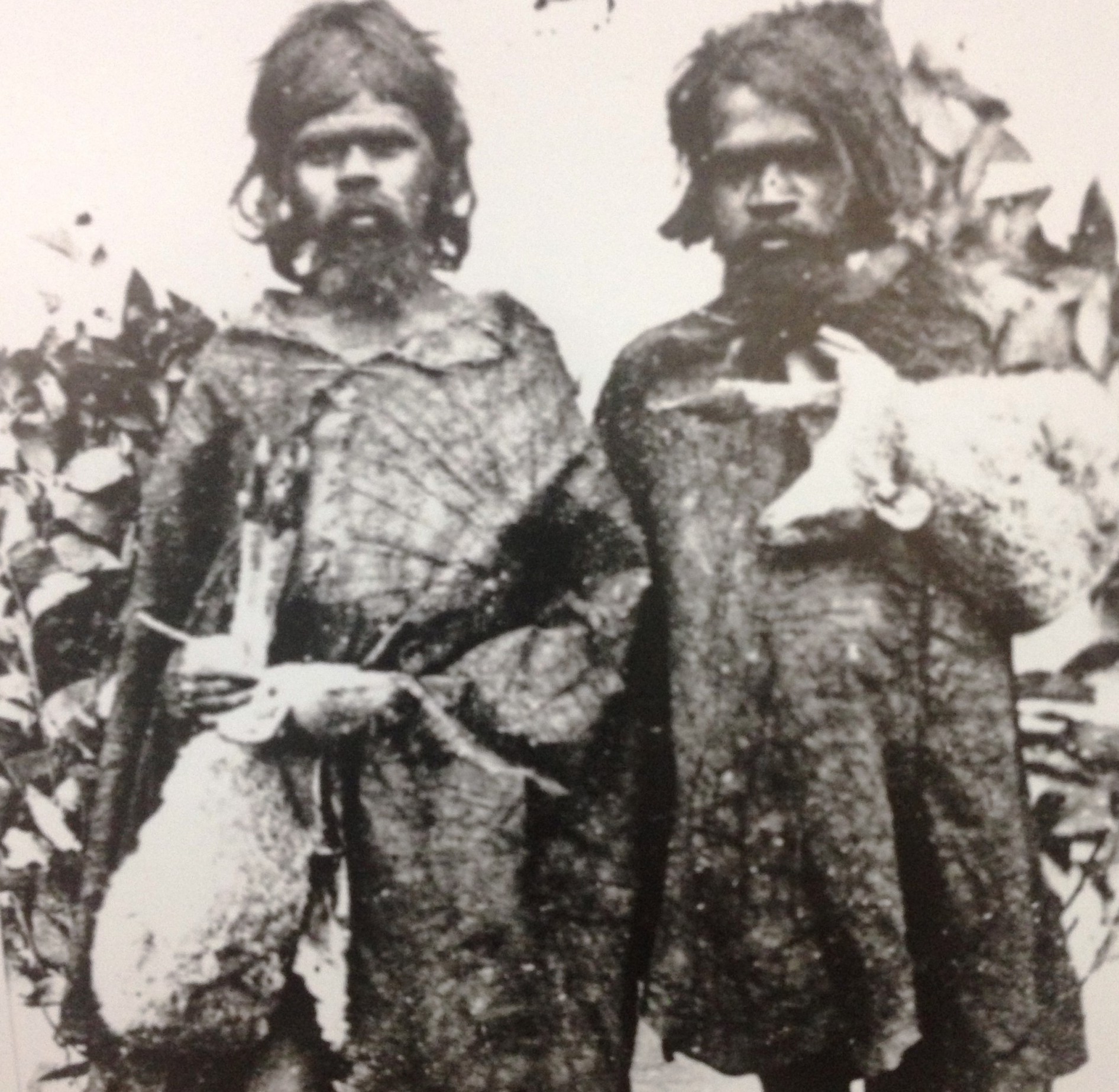

Noongar people were employed as shepherds for European farmers, allowing us to stay on our own country and to live and practice traditional Noongar ways. We let the sheep range freely and relied on our tracking skills to locate the animals and bring them in each afternoon.[xiv]

Noongar women worked as domestic servants in the kitchen and gardens of farmhouses. Usually we lived in humpies or mia mias in the vicinity of the homestead. [xv]

Northam town site evolved, as more settlers took up land. Noongar people moved to camps around the Avon Valley, ‘where they lived on animals and plants that they could find. They also received rations from settlers and the Government’. [xvi]

Fires were a major problem for settlers throughout the 1850s. Many fires were caused by mismanagement or neglect by Europeans. [xvii] It caused severely denuded pastures, unsuitable for stock or crops.

Noongar people would ‘fire the ground’ or set it on fire, as a natural way to regenerate growth and find game, such as kangaroos. This caused enormous conflict with the settlers who did not appreciate (or comprehend) this practice.

Noongar people from the Avon Valley guided explorers travelling inland looking for new pastoral lands.

A report in The Perth Gazette in 1871 [xviii] reflects the attitudes of the time:

A Noongar woman died whilst saving her child from drowning in a well

Pastoralist and writer, Edward Curr referred to the ‘Ballardong or Ballerdokking’ area in his influential four-volume commentary, The Australian Race: Its Origins, Languages, Customs, published between 1886 and 1887.[xix]

The 1891 Census (one of the first of its kind), estimated that 173 Noongar people resided in the Northam -Toodyay region. These figures Noongars take with a grain of salt, as not all Noongars could possibly be recorded.

Noongars mainly earned a living as shepherds or as servants on stations and in homesteads. When pastoral areas were fenced, Noongar shepherds lost their jobs. Many took up work in ‘fencing, clearing, and railway construction works. Others earned a living as kangaroo hunters and police-assistants.’ [xx]

As a sign Noongar lore and custom was still very much vibrant, a big corroboree was held in Northam, near the hospital.[xxi]

1899: A large group of Noongars gathered for another corroboree at the Government Well reserve, one and a half miles from Northam. Most had been shepherding for station owners and they came back to their traditional country where they met other family groups for ceremonies and meetings.

A European observer described the corroborees: ‘Dances were held every evening and they took up a collection from the Europeans who went to watch.’[xxii] About 35 of the Noongars were from the Northam district, the remainder came from Victoria Plains, Newcastle, York, Southern Cross and Coolgardie.[xxiii]

Aboriginal people all over Australia follow this practice of returning to country at periodic intervals for ceremony and cultural reasons. It is often mistakenly referred to as ‘walkabout’ or ‘going on pinkeye’.

A letter to the editor in the Northam Advertiser, calling for sympathy, noted the poor living conditions and health of Noongars.[xxiv]

In 1903, the Chief Protector of Aborigines, Henry Prinsep, moved elderly Noongar people from Northam, York and Beverley to Welshpool Reserve.[xxv] Economic changes in the south had forced more elderly Noongars onto rations. By centralizing the rations at Welshpool, there was further control over Noongar people’s movements.

Northam resident, A.J. Hope, wrote a letter to the council about an Aboriginal burial ground, which was the last resting place for about 20 Noongars. He described an Aboriginal funeral some forty years ago, ‘when the deceased had been buried with all his accoutrements and weapons’.[xxvii] His suggestion to set aside an Aboriginal burial ground between the river and the grass tennis courts in Northam was dismissed.

Chronic unemployment and major disruption to the traditional way of life affected Noongar people who had to rely on rationing to survive.

In response to complaints to A.O. Neville (Chief Protector) from European townspeople, the Premier of WA authorized the entire Noongar population of the Northam district (90 people) to be removed to Moore River Native Settlement by train.[xxviii] In fact, under the 1905 Act, ‘only “Aboriginal natives” and the unemployed were allowed to be removed’. [xxix]

In 1986, Jack Davis wrote the play No Sugar, which documented these events.

3rd May 1940 – The town of Northam was declared ‘an area in which it shall be unlawful for natives not in lawful employment to be or remain’.[xxx] The law was revoked in 1954.

Northam Army Camp was used as a military training centre. It also became an internment camp for Italian prisoners of war.[xxxi] Many Noongar men served in the armed forces.

The Avon River experienced severe flooding in 1945.[xxxii]

In the summer of 1955, the river flooded again, threatening to deluge Northam town.[xxxiii]

Noongar elder, Gus Ryder remembers this well: “All of a sudden when I woke up in the morning… all you could see when you were there, was the leaves of the trees’.

109 Year-old Man Dies

‘Possibly the oldest resident of the Toodyay district, Mr James Gillespie, died in Northam on August 15, aged 109 years.

An [Noongar] Aboriginal, Jimmy Gillespie was widely known and respected throughout the district. He was employed for a greater part of his life on the Wicklow Hills property, which is now owned by Mr E.D.P Hayes.

Mr. Gillespie, whose wife died some years ago, was the father of seven children, two of whom are now deceased.

Mr. Gillespie was the proud possessor of a message from Queen Elizabeth II, following his 100th birthday.’

From the Northam Advertiser, 22 August 1968

The Ballardong claim for Native Title was made in July 2000.

Celebration at Burlong Pool: On July 19th, a group of Noongar people, including Elder, Glenis Yarren, and the Northam Deputy Shire President, unveiled the new interpretive signage acknowledging the area at Burlong Pool as Noongar country.

Located on the Gulga Bilya, Burlong Pool is a special site for the Ballardong Noongar people. The pool has a long history as the summer home of the Waugal. It consists of natural deep water pools 50m wide, one km long and six metres deep.

References

[i] Cummins D, et. al., Report on an Aboriginal site survey of Burlong Pool, Shire of Northam, Perth, Water and Rivers Commission, 1999, p. 18.

[ii] ibid, p. 14.

[iii] ibid p. 18.

[iv] R. Erickson, Old Toodyay and Newcastle, Toodyay Shire Council, Toodyay, 1974, p.1.

[v] Cummins et al., Report on an Aboriginal site survey of Burlong Pool, Shire of Northam., p 18.

[vi] D. Garden, Northam, An Avon Valley History, Northam Shire Council & Hesperian Press, 1992, p2

[vii] S. Hallam and L. Tilbrook, Aborigines of the Southwest Region 1829-1840; The Bicentennial Dictionary of Western Australians Volume VIII, University of Western Australia Press, 1990, p. xv.

[viii] D. Garden, Northam, An Avon Valley History, p 49.

[ix] The Perth Gazette 1.11.1834, p384

[x] N. Green. Broken Spears, Aboriginals and Europeans in the southwest of Australia, Focus Education Services, Western Australia, 1995, p120

[xi] A Hunter, A Different Kind of 'Subject" Aboriginal legal status and Colonial Law in Western Australia, 1829-1861, PhD thesis, Murdoch University 2007, page 135, 139-40

[xii] R. Erickson, Old Toodyay and Newcastle, 1974, p. 43.

[xiii] D. Garden, Northam, An Avon Valley History, p 54

[xiv] R. Erickson, Old Toodyay and Newcastle, p. 64.

[xv] Ibid p. 106

[xvi] Garden p55

[xvii] Ibid p42

[xviii] The Perth Gazette and West Australian Times 1 September 1871, p.3

[xix] E.M. Curr, The Australian Race, Melbourne, Government Printer, 1886-1887

[xx] R. Erickson, Old Toodyay and Newcastle, pp. 340-341

[xxi] D. Garden, Northam, An Avon Valley History, p. 56

[xxii] SROWA, Aborigines Department, Acc 255, 588/1899, R.M. Northam. Reported deplorable condition of natives Northam (from article in Northam Advertiser 17/6 and other transactions with Aboriginal people at Northam)

[xxiii] Garden, p.56

[xxiv] Letter to the Editor - 'The Blacks', Northam Advertiser, 17/6/1899, p.3.

[xxv] A. Haebich, For Their Own Good: Aborigines and Government in the South West of Western Australia 1900-1940, UWA Press, 1992, p. 65.

[xxvi] Annual Report of the Aborigines Department, 1910, p. 20 quoted in A. Haebich, For Their Own Good: Aborigines and Government in the South West of Western Australia 1900-1940, p. 41.

[xxvii] 'Aboriginal Burial Ground', The Primary Producer, 28/4/1927, p. 10.

[xxviii] Haebich, For Their Own Good, p.308

[xxix] Haebich, For Their Own Good, pp.306-7

[xxx] Government Gazette of Western Australia, Perth, Government Printer, 1940, p.663

[xxxi] Register of Heritage Places - Assessment Documentation; Northam Army Camp, Heritage Council of Western Australia, 07/01/2000 online http://register.heritage.wa.gov.au/PDF_Files/N%20-%20A-D/Northam/Army/Camp(P-AD).PDF, accessed on 16/3/2010.

[xxxii] Garden, p.243.

[xxxiii] Garden, p. 253.