Noongar

Amangu – Noongar dialectical group

Yued/Yuat – Noongar dialectical group

Whadjuk/Wajuk – Noongar dialectical group

Binjareb/Pinjarup – Noongar dialectical group

Wardandi – Noongar dialectical group

Balardong/Ballardong – Noongar dialectical group

Nyakinyaki – Noongar dialectical group

Wilman – Noongar dialectical group

Ganeang – Noongar dialectical group

Bibulmun/Piblemen – Noongar dialectical group

Mineng – Noongar dialectical group

Goreng – Noongar dialectical group

Wudjari – Noongar dialectical group

Njunga – Noongar dialectical group

kaartdijin – knowledge

nyininy – sit, sat or sitting

nitcha – this, here

ngulla – our

About Noongar

Noongar means ‘a person of the south-west of Western Australia,’ or the name for the ‘original inhabitants of the south-west of Western Australia’ and we are one of the largest Aboriginal cultural blocks in Australia.

Noongar are made up of fourteen different language groups (which may be spelt in different ways): Amangu, Yued/Yuat, Whadjuk/Wajuk, Binjareb/Pinjarup, Wardandi, Balardong/Ballardong, Nyakinyaki, Wilman, Ganeang, Bibulmun/Piblemen, Mineng, Goreng and Wudjari and Njunga. Each of these language groups correlates with different geographic areas with ecological distinctions. Noongar have ownership of our own kaartdijin and culture. Not all Noongar cultural history and kaartdijin can be shared.

Noongar boodja – country covers the entire south-western portion of Western Australia. The boundary commences on the west coast at a point north of Jurien Bay, proceeds roughly easterly to a point approximately north of Moora and then roughly south-east to a point on the southern coast between Bremer Bay and Esperance. There is no evidence that there has been any other group than Noongar in the south-west. Archaeological evidence establishes that we Noongar – alternative spellings: Nyungar/Nyoongar/Nyoongah/Nyungah/Nyugah and Yunga – have lived in the area and had possession of tracts of land on our country for at least 45,000 years.

Ngulla boodjar, our land, they call this ngulla boodjar our land. Nitcha ngulla koorl nyininy. This is our ground we came and sat upon.

Noongar Elder Tom Bennell in Collard, Harben and van den Berg, ‘Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy’, 2004

Noongar people lived in harmony with the natural environment. Noongar social structure was focused on the family with Noongar family groups occupying distinct areas of Noongar Country. For the Noongar people in the Perth area the main source of food came from the wardan (ocean), the Swan River and the extensive system of freshwater lakes that once lay between the coast and the Darling Escarpment. Further south and east Noongar people lived off the resources of the Karri and Jarrah forests. In the southern coastal area around Albany Noongar built fish traps and hunted turtle. To the north and east Noongar people lived in the semi arid regions of what is now the wheat belt.

It is known that Noongar people travelled within their country to trade with other families. What is now the Albany Highway was once a Noongar track between families in Perth and Albany. Other trade routes existed in the south west and Noongar people could often travel for hundreds of kilometers on foot between each family group.

Noongar people have a long history of culture and tradition and continue to this day to assert their rights and identity in Noongar boodja.

The Tindale Map: Perspectives on the South-West and Noongar Country

Norman Tindale’s map of tribal boundaries was published in 1974. It shows Noongar country as having 14 ‘tribal groups’ with firm boundaries, which form limits of normal social and economic cooperation. Tindale identified communication between the groups through possession of a common language, which has led to them being known as ‘dialectal’ groups of Noongar language.

Maps of the Noongar groups of the south-west often do not contain the word Noongar (or the variants), but the language group names. This mapping of the different Noongar language groups is most associated with the work of anthropologist, Norman Tindale, who was influenced by the earlier work of Daisy Bates.

Norman Tindale is well known for his map of ‘Tribal Boundaries’ (above) based on the work he did in the late 1930s when he established that there are at least 400 – and possibly up to 700 – different Aboriginal language groups in Australia. Published in 1974, Tindale’s map still has great currency and influence. It was used by the Western Australian Government in the Single Noongar Claim to challenge the notion of a single Noongar society.

It should be noted that the term ‘tribal groups’ is not currently used. Much of Tindale’s work was based on earlier writers who used the term, and like all social scientists, Tindale was a product of his time. Hence, Australia, including the south-west, is divided into the ‘tribes’ seen on the map. Today, we identify these 14 groups as sub-groups, or dialectal groups of the larger Noongar society.

The Expedition

In 1938, Tindale began his research as part of the ‘Harvard-Adelaide Expedition.’ He and the members of his team did an enormous amount of travel in their quest to map tribal boundaries across Australia. Because of the sheer size of the project, and with very slow transport at the time, Tindale’s study was hurried. The research for the entire mapping project was done in 18 months.

Tindale visited missions (and government settlements) in the south-west to do his research on Noongar groups. We know he went to Moore River, Gnowangerup and a number of other places. He recorded as much information as he could from the Noongar people who turned up on the day, and others that he was in turn told about.

Norman Tindale’s work was groundbreaking in that it showed Indigenous groups as having territory, geographical interests and country (rather than being ‘wandering’ nomadic people), with boundaries, language and identity. Today, anthropologists see the boundaries (including dialects of language, identity, custom) as far more fluid and malleable with enormous overlap and interchange, just like Noongar society. Many people today still think of Aboriginal people as nomadic or wandering people, when this is not the case.

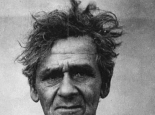

The other members of Tindale’s expedition were interested in things like physical anthropology, so Noongar were measured for skull size and bone length and then photographed. There was little research relating to social custom and no participant-observation field work, where the anthropologists try to get inside the culture and see how people really tick.

One point to make about Tindale’s observations is that, like many of his time, he had a strong patrilineal bias, in that he saw land being transferred through the male line. This naturally influenced his mapping and ignored the fact that Noongar yorgas – women’s lines – were, and are, equally important as men’s.

The most current map we have is called ‘Aboriginal Australia’ and is generally referred to as the Horton Map. It is based on Tindale’s work but is more up to date, as it includes the smaller Indigenous groups as sub-sets of larger societies.