Moora

The town of Moora is firmly situated in Yued Noongar booja – country. Noongar people have lived in this part of booja since the Nyittiny – creation times.

Noongar people believe that the Waugal, the water serpent who created waterways during the Nyitting (Dreaming), rose up from the earth and began his long journey from the north. He came down through Watheroo and Moora, carving out the bed of the river as he went. On his back he carried fish, water snakes, gilgie, turtles and all the creatures of the river. When the Waugal got to Warraminga or Mogumber, he turned sharply west, gouging out deep holes which today are the deepest pools in the river, and what Noongars call “Mur”.

George Fletcher Moore, Advocate General, journeyed north of Perth, exploring and following a large freshwater stream to which he gave his own name – the Moore River. He discovered extensive grassy fertile plains and a fine pool named “Koondaby” or “Candoby” by local Noongars.[ii]

In 1845, conflict developed between European pastoralists and Noongar people in the Moora area when Kabinger, a local Noongar guide (who assisted James Drummond with his botanical collecting expeditions), fatally speared Johnston Drummond at Victoria Plains for having taken his young wife. Two weeks later, Kabinger was shot dead by Johnston’s brother and Police Inspector, John Drummond. Governor Hutt relieved Inspector Drummond of his position in the police force but he was not sent to trial for his crime.[iii]

In 1846, Bishop Rosendo Salvado arrived at ‘Maura’ and established the New Norcia Mission to ‘Christianize and civilize’ Noongar people. Salvado noted of Noongars that ‘every individual has his own territory for hunting; gathering gum and picking up yams, and the rights he has are respected as sacred’.[iv]

1858

A census taken by Salvado of ‘known Aborigines’ from local camping grounds, lists 92 Noongars at ‘Maura’ (New Norcia area), 59 at ‘Wilbing’ (Walebing) and 63 at ‘Bibino’ (Berkshire Valley) [v] Noongars living at Koojan, New Norcia, Walebing and Berkshire Valley supplied labour to the rapidly increasing pastoral and agricultural sector. The Noongar workforce cleared and developed land; along with fencing, shearing, cooking, sowing and harvesting crops for the pioneer Moora farmers.

Midland Railway Company built a station on the Moore River between Midland and Walkaway, near Geraldton. The railway company received 12,000 acres of land for every one mile of railway.[vi] This opened up the land for farming and resulted in the need for a township at Moora.

Objecting to the changes in policy and direction taken by Father Torres, 32 Noongars attacked New Norcia Mission. Father Torres had replaced Bishop Salvado and was ‘unfamiliar with Australia’s colonial history and the cultural needs and expectations of its Indigenous people’[viii]. The new policies he advocated greatly impacted on local Noongar families, on their work and rights to their children. The three Noongar ‘ring leaders’ George Shaw, Emmanuel Jackimarra and Lucas Moody were jailed for three months for planning the attack.

Only ten Noongar people were in regular employment at New Norcia and others were not welcome there at all. The subsequent exodus of Noongar people from New Norcia was ‘unprecedented’ and many moved to places like Moora, Northam and Walebing. [ix]

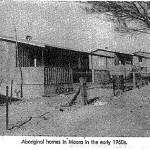

Moora, (being the major town in the Midlands district), attracted the largest concentration of Noongars in the south of WA. Medical attention and rations were also available there. Noongars took part in sporting activities in the town. They worked at the railway yard and on nearby farms.[x] The population of Moora increased four-fold in less than three years, from 60 in 1911 to 240 inhabitants in 1913. However, the Moora reserve lacked basic amenities and soon became overcrowded.[xi] Occupation of the Moora town reserve was short lived, as police and residents opposed the Noongar presence.[xii]

Moore River Native Settlement was established at Mogumber, 50 km south-west of Moora. Opened under the patronage of Chief Protector of Aborigines, AO Neville, Moore River Native Settlement was intended to be a self-supporting farming settlement for 200 Noongar people who were living in camps and around urban centres in the south-west. Originally, it planned to provide schooling for children and employment opportunities for adults, as well as health facilities; though it was chronically under-funded.[viii] Later, it accommodated Aboriginal people from all over Western Australia.

During the early 1920s, the emphasis of Moore River Native Settlement changed from farming to one of internment for Aboriginal people from all over the state. Children of ‘mixed decent’ or what was termed ‘half-caste’ Aboriginal people, were brought there to be trained as domestic servants for white society. They were often taken away without their parents consent and were part of what we now call ‘The Stolen Generations.‘

The Moore River settlement expanded its role into an orphanage, rations depot and home for old persons, unmarried mothers, and the ill. Many older Aboriginal people who were considered too dark to be absorbed into white society were expected to live out their days there. Neville’s view was that as the older people died off the settlements could be closed.[xiv]

In 1922, as a result of complaints by local Moora residents, police ordered Noongars to move to Carramarra, eight kilometres west of Moora but they refused to leave.[xv] Many Noongars moved to Walebing instead, which was preferred because it was a traditional camp. It lay halfway between Moora and New Norcia, where seasonal work could be found nearby. Like most other reserves, it lacked basic amenities. By this time conditions had declined considerably at Moore River Native Settlement. With poor sanitation and increased overcrowding, many health problems were reported.[xvi]Noongar people complained to the Department that they were refused entry to Moora hospital and medical treatment by the local doctor.[xvii]

In 1924, Moore River Native Settlement had an average population of 300 and its buildings were becoming dilapidated.[xviii]

In 1930, following complaints from property owners adjoining the Walebing reserve, A.O. Neville, the Chief Protector, ordered the Noongar residents to move to Moore River Native Settlement. Already forced out of Moora, the Walebing residents refused to leave, claiming they ‘would not find work and would be forced to give up their dogs and horses’.[xix]

The Depression and declining rural economy caused vast unemployment, with Noongars the first to be laid off work. It forced them to rely more on rations, and to be subjected to increasing powers of the police and the Aborigines Department.[xx]

In 1932, Neville applied pressure on Noongar residents camped at Walebing to move to Moore River Native Settlement by restricting rations but they still refused to go. The risk of starvation eventually forced Noongar people to walk from Walebing to Moora where they asked the police ‘for rail passes to Moore River Native Settlement. These were refused so they then had to walk there’.[xxi]

By 1933 the Aboriginal population at Moore River Native Settlement had risen to over 500; while the funds allocated to run the camp had decreased. This flowed on to the amount and quality of food, leading to greater deterioration in the conditions experienced by Noongar inmates.[xxii]

In 1936, Neville again prohibited camping at Walebing in an effort to stop Noongar residents harbouring female escapees from Moore River Native Settlement.[xxiii] The ‘escapees’ were young Noongar girls making their way home to see their families. Despite the pressure, some Noongars remained there, as it was a significant camping place.[xxiv]

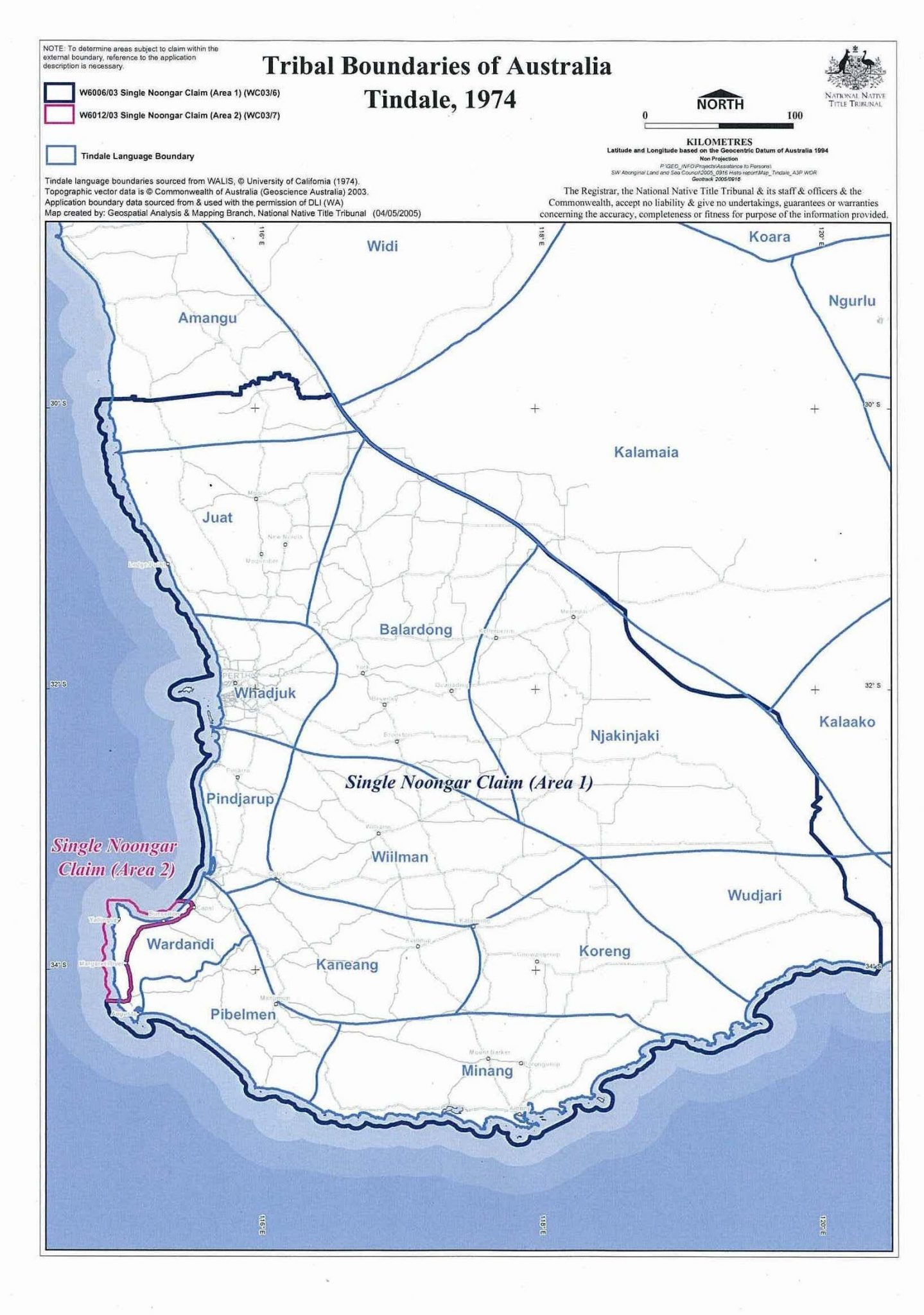

Anthropologist, Norman Tindale, produced a map of the ‘Tribes of Aboriginal Australia’. He established Noongar people as having territory and country, rejecting the theory that they were nomadic. Tindale recorded the local Noongar people living along the Moore River as ‘Yuat‘; a dialectal group of Noongar.[xxv]

In 1951, the W.A. government handed control of the Moore River Settlement to the Mogumber Methodist Mission, who re-named it Mogumber Native Mission.

Between 1918 and 1952, 346 deaths were recorded at Moore River Native Settlement, 42 per cent of whom were children aged one to five. Many died of preventable respiratory disease and infections. By way of comparison, five times more money was spent on prisoners at Fremantle gaol than was spent on the Aboriginal inmates at Moore River Native Settlement.[xxvi]

In 1953, a reserve three kilometers south of Moora was established for Noongar families displaced from Moore River Native Settlement.

In 1965, the Department of Community Welfare built four houses in Moora for Noongar people from the reserve. Three Noongar families moved to the Clarke Street houses.

In 1974, the Central Midlands Aboriginal Progress Association was established by Beverley Port Louis. Its aims were to promote the development of Aboriginal communities, including self- support programs. This incorporated economic and health projects, as well as building trust between Noongar people and Europeans.[xxvii]

In 1978, the Moora out of town reserve was closed and people were moved into Moora. see article

The Yuat community artefacts group was established in Moora by the late Ned Mippy and the late Ben Drayton. The vision of its creators was to preserve Indigenous cultural identity, create employment, and provide a solution to racial tension and social problems.[xxviii] Ned Mippy’s biography

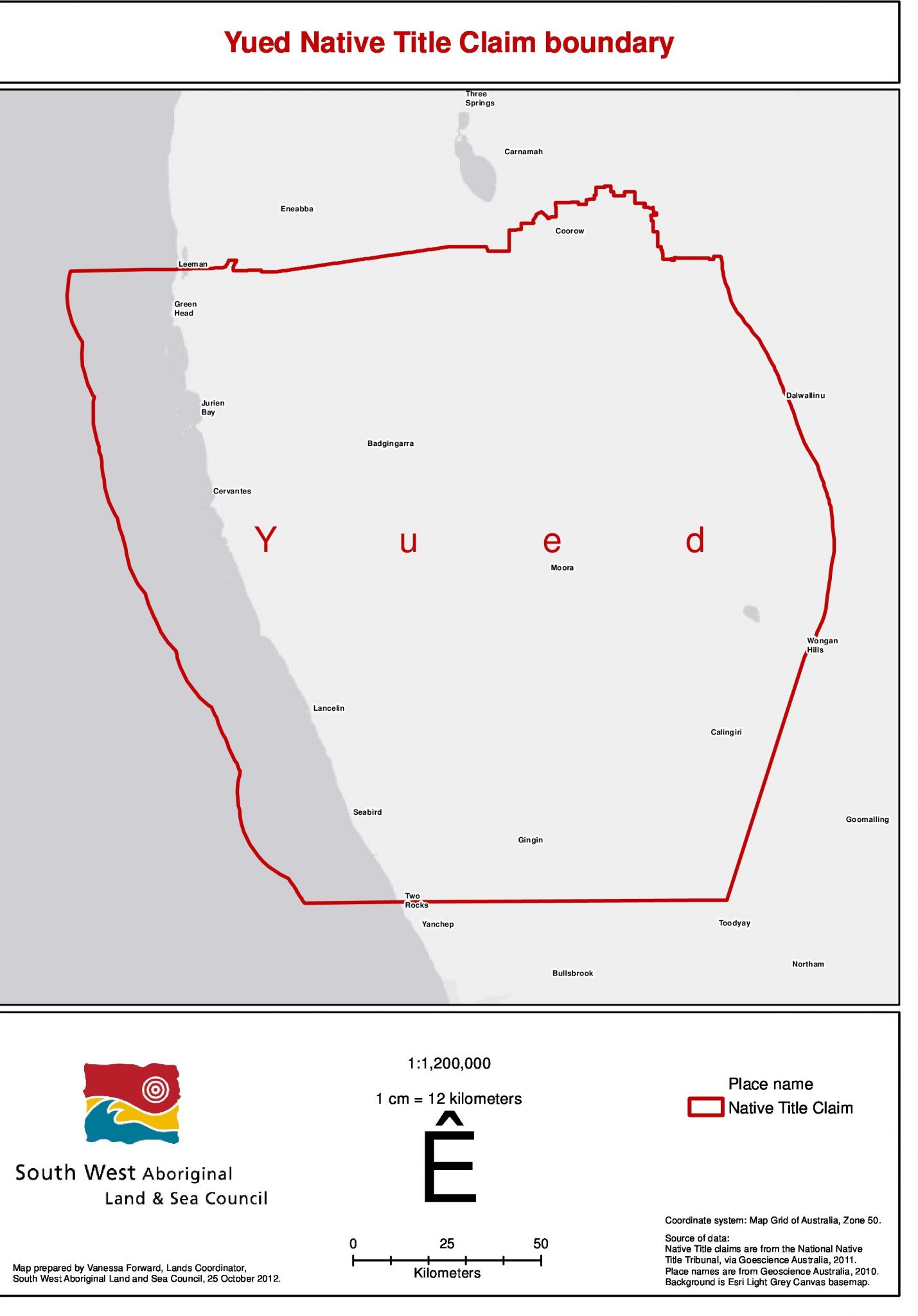

On the 22 August 1997, local Noongar people united to lodge a Native Title Claim over 29,253 square kilometres, including the town of Moora.

On the 16 September 2006, the Supreme Court ruled the Noongar people and their customary title to land had survived, despite disruption and government policy.

References

[i] Landgate, http://www.landgate.wa.gov.au/corporate.nsf/web/History+of+country+town+names (accessed 18 October 2010)

[ii] G.Moore, (1884a). Diary of ten years: eventful life of an early settler in Western Australia. London, Walbrook.

[iii] N. Green, Aborigines and White Settlers in the Nineteenth Century, in CT Stanage (ed), A New History of Western Australia, UWA Press, Nedlands,1981

[iv] R. Salvado (1851), The Salvado Memoirs: historical memoirs of Australia and particularly of the Benedictine Mission of New Norcia and of the habits and customs of the Australian natives by Rosendo Salvado; translated and edited by E.J. Stormon. Nedlands, W.A : University of Western Australia Press, 1977, pp 130-131

[v] N. Green and L. Tilbrook, Aborigines of New Norcia 1845-1917: The Bicentennial Dictionary of Western Australia, Volume 2, University of Western Australia Press, 1989, pp206-212

[vi] Shire of Moora website: History of the Shire of Moora: http//www.moora.wa.gov.au (accessed 18/11/10)

[vii] A. Haebich, For Their Own Good: Aborigines and Government in the Southwest of Western Australia, University of Western Australia Press 1988, p. 83.

[viii] B. Rooney, The Legacy of the Late Edward Mippy: An Ethnographic Biography, PhD Thesis, Curtin University, March 2002, p. 149

[ix] Haebich, 1988, p.19, Rooney (2002) pp 150, 152.

[x] Haebich,1988, p.133

[xi] Ibid, p.132

[xii] Ibid, p.232.

[xiii] For histories of Mogumber see: S. Maushart, Sort of a Place Like Home: Remembering the Moore River Native Settlement, Fremantle, 1993. A. Haebich 'On the Inside: Moore River Native Settlement in the 1930s', in Gammage, B. and Markus, A. eds, All That Dirt: Aborigine 1938, Canberra, 1982. A. Haebich and A. Delroy, The Stolen Generations, 1999. A. Haebich, 'Twilight of Knowing: The Forgotten Australian Debate', in Overland 170, Autumn 2003. A. Haebich, For Their Own Good, 1988. A. Haebich, Broken Circles: Fragmenting Indigenous Families 1800-2000, Fremantle, 2000. A. Haebich, 'Between Knowing and Not Knowing: Public Knowledge of the Stolen Generations', in Aboriginal History, 25, 2001.

[xiv] A. Haebich, For Their Own Good, 1988, pp 174, 178-187, 193-194, 206, 211-212, 216 250, 251, A. Haebich & A. Delroy. The Stolen Generations: separation of aboriginal children from their families in Western Australia. Western Australian Museum, 1999, p.28

[xv] Haebich, 1988, p.144

[xvi] Ibid pp, 184, 192, 219-220, 253-254

[xvii] Ibid, p.236.

[xviii] Haebich, A. For Their Own Good, 1988, p.252

[xix] Ibid p.291

[xx] Ibid p 290

[xxi] Ibid p. 291

[xxii] A. Haebich, For Their Own Good, 1988. pp.310, 311. A. Haebich & A. Delroy, The Stolen Generations, p.32

[xxiii] Ibid, p. 313.

[xxiv] Rooney (2002) p.157; Haebich pp 290-1.

[xxv] See 'About Us' on Tindale

[xxvi] A. Haebich For Their Own Good 1988. A. Haebich & A.Delroy, The Stolen Generations. p.32

[xxvii] The West Australian: Report on the Central Midlands Progress Association. 14/7/1984

[xxviii] Rooney (2002), p.212