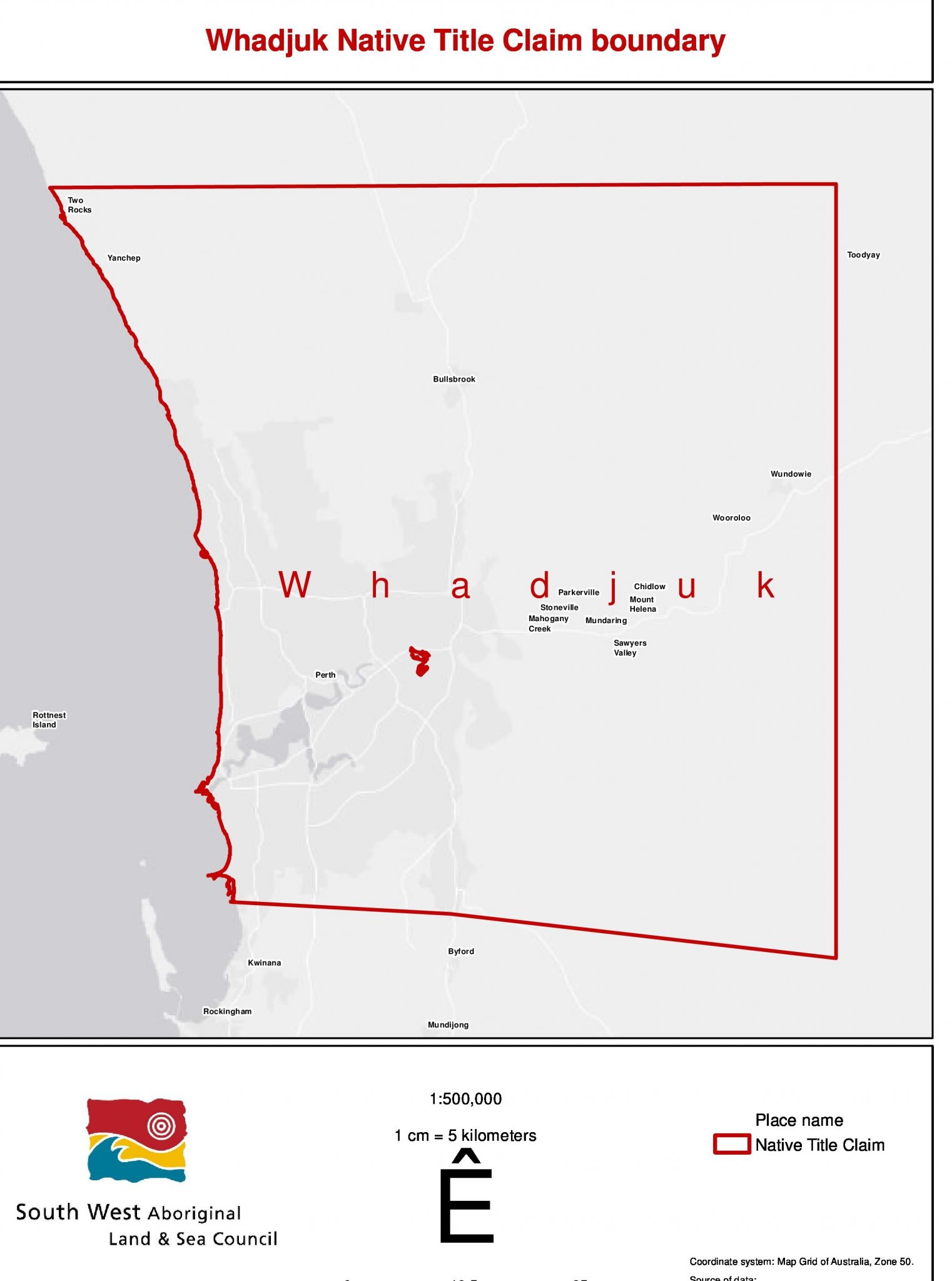

Whadjuk

Guildford is firmly situated in Whadjuk Noongar booja – country. Noongar people have lived in this part of booja since the Nyittiny – creation times.

The town of Guildford in the Whadjuk region has always been an important meeting place for Noongar people. The area contains many campsites and spiritual sites which have been used by Noongars from pre-contact to the present day.

One of these spiritual sites is a bend in the Swan River near Success Hill, where the Waugal lives.[i] Central to Noongar culture and beliefs, the Waugal is the serpent that created the Swan and Canning Rivers. It meandered over the land of the south-west, making curves and contours of the hills and gullies.

Guildford and the surrounding areas of Success Hill and Pyrton sit on pivotally important Noongar country where the Swan meets the Helena River. To Noongar people it is known as Yellagonga’s country (west of the Swan River) and Weeip’ country (east of the Swan). The Helena River was a moort bidi – a main run for Noongar people going to and from Guildford where coroborrees were performed.

When Captain James Stirling explored the Upper Swan River in March 1827, he had little contact with Noongar people but was amazed at the ‘park-like landscape’, which was created by Noongar fire-stick farming.[ii] Traditionally, Noongar people burn sections of dry bush before the rainy season to encourage re-growth of sweeter grasses. Fire-stick farming also enabled easier hunting of kangaroos and other animals.

In 1829, over 600 Europeans or wadjelas, as they are known to Noongars, arrived at Fremantle and the Swan River Colony was established. Guildford became an important market town for Europeans, and Noongar lands, particularly around the Swan River and Guildford, were subsequently taken over by the wadjelas.

As the Guildford area was a traditional Noongar meeting place, there was a good deal of contact between Noongars and wadjelas. This often turned to conflict, with the clash of traditional Noongar practices of hunting and gathering, and European ways of farming. The main cause of much of the conflict between Noongars and Europeans was the different and often incompatible values held about the nature of land ownership and property. [iii] Noongar people do not think of the land as owning it, we consider it to be a part of us.

Midgegooroo, a senior and respected Noongar man, caused the new settlers considerable grief by attempting to resist their settlement of his country. After many confrontations he was caught and executed outside Perth gaol in May 1833. Recently, the lost burial site of Midgegooroo was located at the Deanery on St. Georges Terrace in Perth city.[iv]

Midgegooroo’s son, Yagan – the Noongar resistance leader – was shot by a young bounty hunter on the Upper Swan a few months later. Yagan was both respected and feared by Europeans, and some were angry at the way in which Yagan had been entrapped and killed.[v] For Noongar people, Yagan is a symbol of resistance to European colonization and culture.

Early settler, Edward Hamersley, bought the properties Pyrton and Lockridge to the north of Guildford in the 1840s, and like other pastoralists, employed Noongar workers. The land was and is significant for Noongar people, encompassing traditional camp sites around Success Hill and Bennett’s Brook.[vi] Noongar families continued to live on this private land, away from the control of the Native Welfare Department and the Bassendean Roads Board for almost one hundred years.[vii]

In 1842, George Fletcher Moore, Advocate General and a farmer who lived in the Upper Swan, published A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia. Moore recorded a great deal of information about Noongar people’s lore and customs and their relationship to the land.

George Fletcher Moore’s book available to view on Google Books

Despite Europeans claiming the land, Noongar people set up semi-permanent camps to the north of Guildford and around the traditional meeting ground at Success Hill. For the most part, Noongars held onto our traditional ways and resisted attempts by European landowners to turn us into a servile class.[viii]

In 1851, the Convict Depot was established in Guildford and over the next 18 years a total of 9,000 men arrived in the colony.[ix] The convicts, and later, ‘Ticket of Leave’ men (who had been granted parole), began to live and work in Guildford, building roads, houses, bridges and other public works.

Enrolled Pensioner Guards, who supervised convict labour, settled on land grants in West Guildford. The grants were smaller land holdings of fenced two acre lots. [x] This expansion of European settlement forced more Noongars off our country.

In 1901, when the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York visited WA, 110 Aboriginal people from the south-west were brought to West Guildford and camped on Old Guildford Road. They held corroborees and went sightseeing, which included a visit to the zoo.[xi]

At the end of 1903, the Chief Protector, Henry Prinsep decided to make Welshpool Reserve a ration depot. The reserve had been developed in 1899 as a small scale agricultural settlement for local Noongars. Prinsep insisted all Noongar people in the metropolitan area should be moved to the reserve, along with a European caretaker. Despite protests from the residents, Noongars from Guildford, Perth, Helena Valley, Gingin, Northam, York, Beverley, Busselton and Pinjarra were moved there. However, most only stayed a few years, and by 1908 the reserve was deserted.[xii]

In 1908, Welshpool Reserve closed and some of the former Noongar residents went to an old camping ground in West Guildford but they were soon moved by police to Success Hill.[xiii]

In 1910, Noongars camping at Success Hill were moved to the newly created reserve in South Guildford, which later became Allawah Grove.[xiv]

Noongar people also camped on farms along the Swan River. They chose sites, as had always been the practice, near good water supplies, such as springs (jump-ups) and streams.[xv]

As a result of the government’s agricultural development programs, town reserves became the focus of the Noongar way of life. This had many negative effects on Noongar people, eroding our traditional practices and culture. Yet, historian Anna Haebich wrote that: ‘Related families frequently visited between reserves, sharing companionship, food and entertainment’… ‘Dances, accompanied by a piano accordion, were often held around the camp fires at the reserves’.[xvi]

In 1921, the Repatriation Department claimed Hamersley’s Pyrton Estate to convert to farms for returned soldiers. Pyrton Estate had been an important camping site for local Noongar people, and this created conflict when they were forced to leave.[xvii] Before the reclamation, Noongars had moved into the Guildford area each year for the grape and fruit picking season. They camped on the Pyrton Estate, and family and friends from the Beechboro and Lockridge camps often visited on weekends.’ Other camps included Guildford Bridge; Middle Swan Bridge; Upper Swan Bridge; Copely Road, Upper Swan; Jane Brook, Middle Swan; Benara Road area; and near the Helena River Bridge.[xviii]

In 1928, William Harris, a leader and civil rights advocate, led a deputation to the Premier of W.A., calling on the State Government to repeal the 1905 Act. Harris had been a private pupil at the “Swan Native and Half-Caste Mission” in Perth. He was a significant campaigner for Aboriginal civil rights and fought for over 22 years for Noongar people affected by the restrictions of the 1905 Act.[xix]

Military Forces took over Allawah Grove Reserve in South Guildford to use as an army camp. There was little or no alternative accommodation provided for Noongar people, who had no option but to move to relatives in Eden Hill.[xx]

In 1945, a proposal by the Church of Christ to build an Aboriginal Hostel in Mary Crescent, Bassendean was rejected, following a petition with 95 signatures to the Bassendean Road Board.[xxi]

After the tough years of the Depression, work was more plentiful for Noongar people during the war years.

Many Noongar people lived in houses made from natural or recycled materials used in traditional ways. These included forked branches covered with tin, hessian bags or brush, as well as tents and tin shacks.[xxii] These kinds of houses maintained Noongar links to traditional living and were often in contrast with the European view: Southern Districts Officer, C. Wright Webster described ‘the housing conditions in this area as deplorable, and the worst he had seen anywhere’. He said that ‘Aboriginal people tend to be housed in mia mias, bag humpies, beaten tins on wooden framework, or dilapidated timber shacks with iron roofs. The most common type of dwelling is the tent’.[xxiii] Despite this, many Noongar people fondly recall those days when extended family groups lived together.

Forty adults and 90 children from Allawah Grove moved into new homes in suburbs such as Balga, Hamilton Hill, Gosnells and Coolbellup. Only so-called ‘genuine’ residents of Allawah Grove were given houses.[xxiv] By January 1969 there were 31 Noongar people still living at Allawah Grove, despite the electricity, water and sewerage having been disconnected. The huts were destroyed in February 1969.[xxv]

1972

In 1972, an Aboriginal consulate was set up on Parliament House lawns to draw attention to the lack of housing for Noongar people in the metropolitan area. At the time, about 60 Noongars lived in camps around the Guildford area, in bush along Kalamunda Road and Lockridge, and near the Midland abattoir.[xxvi]

The closure of many Aboriginal Reserves in the 1970s and the problems moving Noongar people into State housing in the metropolitan area, meant there were many homeless Noongars sleeping in parks, under bridges, in cars and near the river in the Swan Valley.[xxvii] After campaigning since 1977 for Noongar people to live on our own terms, the Fringe Dwellers of the Swan Valley received title to land at Lockridge in 1994.[xxviii]

On 19th Sept 2006, the Federal Court brought down an historic judgment in favour of Noongar Native Title over the Perth metropolitan area: it is known as Bennell v State of Western Australia [2006] FCA 1243. Justice Wilcox found that Native Title continues to exist within an area in and around Perth. This is the first judgment which recognised Native Title over a capital city and its surroundings.

Evidence in support of this claim was heard at Guildford – the very same site where Noongars camped at the time of Europeans claiming our land. Justice Wilcox found the Noongar community had continued to exist and still practice many of our lores and customs. We did so despite the disruption resulting from being forced off our land as a consequence of white settlement and Government policies.

References

[i] 'Appendix 1', in Guildford Study Group for the Shire of Swan, 'Guildford: A Study of Its Unique Character', 1981, pp.iii-v

[ii] S. Hallam, 'Fire and Hearth: A Study of Aboriginal Usage and European Usurpation in South-Western Australia, Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1979, pp. 5, 11, cited in J. Carter, Bassendean: A Social History 1829-1979, Town of Bassendean: Perth, 1986, p. 16;. See also Stirling to Darling 18 April 1827, HRA, Series 3, Vol. 6, p 557.

[iii] N. Green, Broken Spears, Focus Education Services, Cottesloe, Western Australia, 1984, p54

[iv] The West Australian, 4 September 2010

[v] The Perth Gazette, 20 July 1833.

[vi] Hamersley Papers, Battye Library, cited in J. Carter, Bassendean : A Social History 1829-1979, Perth, W.A : Town of Bassendean, 1986, p.52;

[vii] Hamersley, correspondence, 25/5/1990, original held DIA, correspondence file 193/86, vol. 17, fol. 20-27, now SWALSC file RES003-06, Bennett Brook camp area 3840; Jennie Carter, Bassendean : A Social History 1829-1979, Perth, W.A : Town of Bassendean, 1986, p.245

[viii] J. Carter, Bassendean : A Social History 1829-1979, Perth, W.A : Town of Bassendean, 1986, pp.52,53

[ix] Ibid pp53-.54

[x] Ibid p55

[xi] Aborigines Department Annual Report, 1902, p.9, cited in A. Haebich, For Their Own Good, Aborigines and Government in the Southwest of Western Australia. University of Western Australia Press 1992, p.6

[xii] A. Haebich 1988 pp.64-5;

[xiii] P. Biskup, Not Slaves, Not Citizens, University of Queensland Press, 1973, pp.120-121

[xiv] Ibid p.121

[xv] Judy Hamersley, correspondence, 25/5/1990, original held DIA, correspondence file 193/86, vol. 17, fol. 20-27, now SWALSC file RES003-06, Bennett Brook camp area 3840

[xvi] Haebich,1992 :pp240- 241

[xvii] Ibid pp.230-232.

[xviii] PR Barker, Report of Survey amongst Indigenous People living in the Midland area, 23/3/1972; The West Australian, 25 July 1968

[xix] L. Tilbrook, Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 9, Melbourne University Press, 1983,pp 213-214

[xx] J. Carter, Bassendean : A Social History 1829-1979, p.243

[xxi] Ibid pp.243,245

[xxii] Annual Report of the Commissioner of Native Affairs, 1950, p.10.

[xxiii] Ibid p.10.

[xxiv] The West Australian, 27/11/1968, 3/1/1969

[xxv] Ibid. 8/1/1969

[xxvi] Daily News, 21.6.1972

[xxvii] S. Delmege, 'The Fringe Dweller's Struggle: Cultural Politics and the Force of History, PhD thesis, Murdoch University, 2000, p.203.

[xxviii] Ibid, p.202.